Editor’s Introduction:

“Anzaldúa’s approach to writing was dialogic, recursive, democratic, spirit-inflected, and only partially within her conscious control. She relied extensively on intuition, imagination, and what she describes in this book as her “naguala.”” [guiding spirit]

“She wanted the words to move in readers’ bodies and transform them, from the inside out, and she revised repeatedly to achieve this impact. She revised for cadence, musicality, nuanced meaning, and metaphoric complexity.”

- Anzaldúa worked with her spirituality as way for epistemological and ontological decolonization.

- “Anzaldúa call[ed] for a new aesthetics, an entirely embodied artistic practice that synthesizes identity formation with cultural change and movement among multiple realities.”

- focus on “gestures of the body” — theories that stimulate, create, and in other ways facilitate radical physical-psychic change in herself, her readers, and the various worlds in which we exist and to which we aspire — looks at imagination as intellectual-spiritual faculty.

- interweaving the personal with the collective — ethics of interconnectivity — reaching through the wounds to connect with others (p 25)

- On healing, she writes, “My job as an artist is to bear wit ness to what haunts us, to step back and attempt to see the pattern in these events (personal and societal), and how we can repair el daño (the damage) by using the imagination and its visions. I believe in the transformative power and medicine of art.” (p 34/xxxii)

- Anzaldúa viewed indigenous thought as a foundational, vital source of decolonial wisdom for contemporary and future life on this planet and else where — respectfully borrows from Mexican indigenous traditions. (xxxiii)

Anzaldúa on autofiction: “I am the one who writes and who is being written.” (Gestures of the Body, 3). I am inspired by and relate to this practice. I do a lot of this in my narrative projects, as well as the practice of relating to other people.

“Sometimes the shadow blocks this process and rules my behavior, making the process painful.” (4) — magical thinking

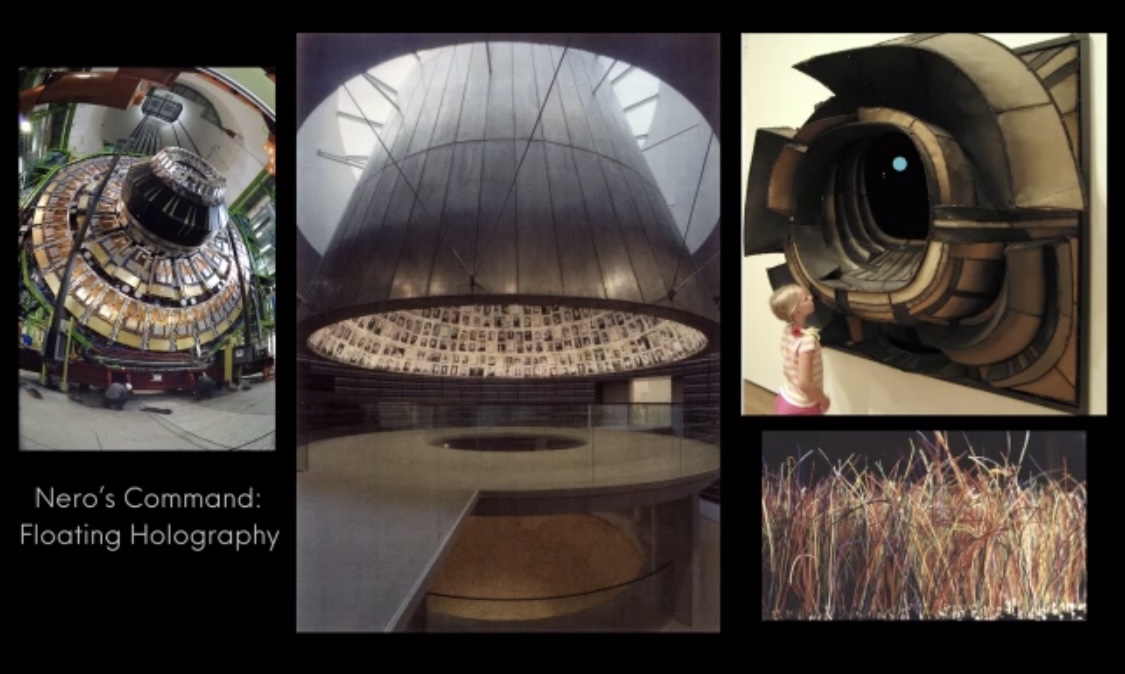

p 5. Imagination — (the psyche’s image- creating faculty, the power to make fiction or stories, inner movies like Star Trek’s holodeck)

A lot of what she’s writing about I have been doing intuitively, like inscribing (with zines –words, images, movies, music etc.) — it makes me think about the mergence of the personal and collective conscience.

p 6. “I treat each essay as “story” with antagonism, dialogue, crisis, climax, resolution, and poetics.”

“Through narrative you formulate your identities by unconsciously locating yourself in social narratives not of your own making.” — I am interested in the dark side of this; like being pulled into a narrative I don’t necessarily relate to just because I identify with a certain ethnic origin in terms of being placed on a larger system of hierarchal organization in white-dominated spaces. Anzaldúa speaks of similar struggles, but in terms of legitimizing yourself for women of color, queers and othered groups — I am against academia in this regard; I don’t necessarily agree with being bound to a narrative I don’t fully own yet, or might never — again the problem of the romanticization of suffering, pain, and misery — something that is inherent in the art world, museum spaces, and basically any institution that has been white/male-dominated — the looking down upon: Look at Martha Rosler’s photography and the issue of documenting people at their worst for the sake of the art, with the subject becoming othered in the process itself — it serves a white audience, mostly not even eliciting empathy but profit from the marginalization, institutionalization, and further separation of the other-ed subject.

She goes on to say that your culture gives you your identity story.

p 7: “rewriting narratives of identity […] attempts to revise the master story.”

7-8: “My dilemma, and that of other Chicana and women-of-color writers, is twofold: how to write (produce) without being inscribed (re-produced) in the dominant white structure and how to write without reinscribing and reproducing what we rebel against. Our task is to write against the edict that women should fear their own darkness, that we not broach it in our writings. […] Our task is to light up the darkness.”

10. we must look at the shadow — Abre los ojos, North Ame rica; open your eyes, look at your shadow, and listen to your soul. (p. 11)

11. “Afghani women became almost the poster child for women’s oppression in the Third World,”

White savior complex — profiting from victim mentality — war-for-profit mongers pushing a nation-sponsored “war against terrorism”; “To boost his cowboy self-image, Bush comes riding on his white horse, a gunslinger at high noon, bragging that he’ll bring in Osama bin Laden “dead or alive” and save the world for us.” (p. 13) — from emancipation from Third World culture, saving these women behind veils whom our policies silenced to begging in the streets (p. 13) — later references to the nation as a powerful horse and him riding it badly (p. 16)

I don’t get why I’m doing the white person’s job of reflecting on their behalf when I could be using this time for my own self-improvement. A lot of this white-savior mentality reflects in the youth as well, people who aren’t policy makers.

A lot of this is still very relevant in this moment of time as we are living it right now, which is also insane — nothing remains changed. What is the point of academia? Is it pacifying us? What will the discussion of this in a classroom do when there are people dying on the Gaza Strip right now as we speak — it is the institutionalization of intellect in a white-dominated space filled with white tears for all the white guilt from stealing our money so we can be saved from the third culture that binds us — is it not history repeating itself? We remain stuck in a time loop, unable to move forward — how will today’s education save us from ourselves as we assimilate into a system that murders? We have become the murders — you, me, the land we occupy and pay our rents for — we are fueling wars. And we remain passive. We kill children. Women. Men. Soldiers and terrorists alike. We are the murderers. We are the murderers. We are the murderers. We are the murderers. We are the murderers. We have assimilated. May the devil bless us and this institution that saves us from our culture and assimilates us into a whiter, better world. Oh, the bloodshed. Oh, the bloodshed. Can you feel your skin as your blood boils? Does it not? Have you assimilated yet? RED. All I see is red. MURDER. MURDER. MURDER.

Oh, save us from the world outside! The terror! Take our money! Pacify us!

Murder. I see bodies lined up.

Murder.

Yes. More murder.

MURDER!

Week 8

I was really inspired by Guadalupe Maravilla’s sculptural practice — his shrine of acoustic meditation (Disease Throwers) series is visually powerful, along with the message it symbolizes. It all goes to show how the work ties together with the reading: In Chapter 5 of Anzaldua’s reading “Putting Coyolxauhqui Together: A Creative Process”, she writes about the work of embodying consciousness and easing tension out of the body (pg 105).

“You invoke this sentience to help you, not to transcend but to more passionately embrace the physical. You metamorphose into someone else” — she goes on to talk about the mask versus internal experience, emotional state/mood (105).