生之途,必磨難艱辛;狂風颳折,暴雨淋摧。然於千破碎處,常藏再生之勇。是時,我等非悼終結,實祭奠新生。

On the journey of life, challenges and hardships are inevitable; fierce winds bend and break, storms drench and destroy. Yet, within the myriad fragments of brokenness, resilience often hides, a courage perpetually poised for rebirth. At this juncture, we do not lament an ending, but solemnly commemorate a beginning.

I. Academic Reference and Inspiration

My job as an artist is to bear witness to what haunts us, to step back and attempt to see the pattern in these events (personal and societal), and how we can repair el daño (the damage) by using the imagination and its visions. – Anzaldúa G., Light in the Dark (2015)

Forewords – Art and Trauma

Art can be defined as a creative, expressive activity in which thoughts, feelings, ideas or perspectives are expressed through a variety of media and forms. The purpose of art is usually to inspire the viewer or audience to think and to evoke emotional resonance. As for trauma, it can be regarded as a miserable experience that is a response to an event or series of events that are emotionally painful, distressful, or shocking, which often results in lasting mental and physical effects. As the saying by Anzaldúa goes, “My job as an artist is to bear witness to what haunts us, to step back and attempt to see the pattern in these events (personal and societal), and how we can repair el daño (the damage) by using the imagination and its visions.” This can be said to precisely convey the central thought of our project: we, as the creators, want to transform the idea of a variety of traumas which we have learned in classes into a series of artwork that can trigger our viewers’ reflection.

On the basis of such mentality, in the stage of idea development for this theme, we came up with the following two concepts; despite the final decision of no direct incorporation of these two concepts with our performance, we would still list them here for reference.

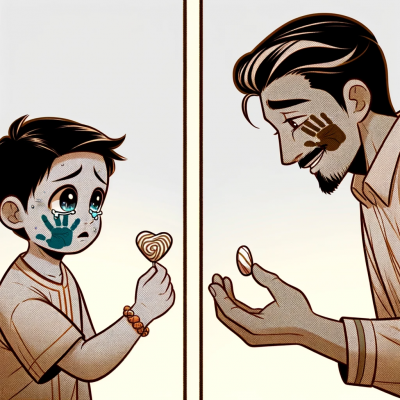

Vicious Cycle – 「打一巴掌,給一顆糖」

(“Da Yi Ba Zhang, Gei Yi Ke Tang”, Slap someone in the face and give a candy right after)

Jerrold

This is a complexed condition we came up with when we thought of the incident that cause trauma but with pleasure at the same time.

Baumrind defined three specific parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive. And subsequent research scholars have suggested adding a fourth: the uninvolved parenting style. The influence of parenting styles on children’s psychological development and growth is profound, particularly within East Asian cultures. The “打一巴掌,給一顆糖” (“Da Yi Ba Zhang, Gei Yi Ke Tang”, Slap someone in the face and give a candy right after) approach, combining traditional methods with this distinct parenting style, forms a unique child-rearing model. This approach emphasizes discipline and achievement while attempting to balance strict discipline with rewards. However, this method may lead to unintended psychological consequences, especially concerning childhood trauma and the dynamics of the original family.

Traditional East Asian Family

In contexts where the participants are exclusively from East Asian backgrounds, discussions of trauma often immediately evoke the concepts of “original family” and “childhood trauma.” The family seems to be the starting point of trauma for East Asian children. The emergence of this perception might be attributed to the globally recognized “Asian parental discipline style.”

Traditional East Asian education places greater emphasis on collective values, respect for elders, and academic performance. The love of East Asian parents for their children is somewhat paradoxical. As I expressed in the class: “Love is kidnapping.” On closer examination of the parent-child relationship in East Asian families, it is evident that parents often act as the law-makers within the family unit, while children tend to be the followers. “Children are taught to suppress aggressive behavior, overt expressions of negative emotions, and personal grievances; they must inhibit strong feelings and exercise self control in order to maintain family harmony.” (Chan, 1986)

How to understand “打一巴掌,給一顆糖”

The phrase “打一巴掌,給一顆糖” (“Da Yi Ba Zhang, Gei Yi Ke Tang”, Slap someone in the face and give a candy right after) symbolizes a relationship dynamic where an individual first harms and then offers benefits to gain forgiveness. Commonly observed in professional settings between superiors and subordinates, this approach has also been likened to a literary technique of creating tension before offering relief. However, statements in this category seem to seek a presentation of results at the expense of process. When applied to child-rearing, this method raises significant concerns.

Long-term strict discipline, especially when coupled with emotional neglect or inconsistency, can lead to childhood trauma. In the “打一巴掌,給一顆糖” parenting model, children may feel confused and insecure due to the unpredictability of their parents’ behavior and responses. This uncertainty and emotional fluctuation can lead to anxiety and issues with self-worth. Additionally, the excessive focus on achievement within this model can cause immense pressure and feelings of failure when children do not meet expectations.

Furthermore, reconsidering the parent-child relationship within this dynamic is crucial. Here, a parent asserts dominance through discipline and then offers consolation, questioning whether the consolation remains genuinely comforting. Superficially resembling the authoritative parenting style, this approach is actually a covert form of authoritarian parenting. All principles are set unilaterally by the parents, with both punishment and reward stemming from their discretion. Thus, what appears as authoritative parenting is, in essence, a veiled form of authoritarian parenting.

Turning into Visual Art

Initially, our intention was to conceptualize the phrase “打一巴掌,給一顆糖” (“Da Yi Ba Zhang, Gei Yi Ke Tang”, Slap someone in the face and give a candy right after) into a visually impactful meme or comic strip. The proposed imagery involved a child with a vivid slap mark on their face, tears in their eyes, reaching out to accept a candy offered by an adult. Upon closer inspection, the adult, smiling, also bears a faint slap mark on their face.

The slap mark on the child represents the trauma inflicted by this parenting approach, while the adult’s slap mark suggests that such trauma does not simply fade with time. Instead, it diminishes in intensity but persists in a particular form, perpetuating and replicating itself in subsequent generations. This visualization serves to illustrate the cyclical nature of this trauma within the familial context.

Beauty in Repair – 「金継ぎ」(Kintsugi)

Jean

Kintsugi (Gold Rejoining), or Kintsukuroi (「金繕い」, Gold Repairing), is a traditional Japanese art form that involves repairing broken pottery or ceramics using lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. Instead of disguising the fractures and flaws, Kintsugi accentuates and celebrates them. This technique was said to be invented around late 16th century when the Momoyama Period (桃山時代) took place, when Chanoyu (茶の湯, Tea Ceremony) started to become popular within Japanese royalties, and utensils of which was created with Maki-e (蒔絵, Lacquer Decorative Art), believed to be the origin of the Kintsugi technique.

The spirit behind Kintsugi is rooted in the idea of embracing imperfections and acknowledging the history of an object, recognizing that breakage and repair are an integral part of its life. As the Japanese saying goes, “形あるもの全て壊れる (‘Katachi arumono subete kowareru’, Everything that has a shape breaks)”, this humbleness, gentleness, and optimism toward the in Japanese philosophy are explicitly showed; sometimes being harmed is unavoidable, but one always has the right of choice in how to treat their wounds.

As the repaired piece becomes a unique work of art, with the golden seams or lines creating a visually striking contrast against the backdrop of the ceramic surface. Kintsugi not only restores the functionality of the object but also elevates it to a new level of beauty, symbolizing resilience, acceptance of change, and the beauty of impermanence. This ancient Japanese art form carries a profound aesthetic and philosophical significance, encouraging a perspective that values the history and experiences embedded in the broken and repaired aspects of life.

We originally planned to find some paper containers and intentionally tear them into several parts, then paste it back together and tracing the torn patterns with golden paint. (We did not consider using a genuine ceramic container due to budget and safety concerns.) However, this aesthetic concept offered us inspiration of cutting parts of everyone’s identity photos and put them together into a collage, conveying the sense of both brokenness and fullness.

In the Form of “Funeral”

Jean

Individuals, with their unique experiences and histories, come together to form collectives, which in aggregate shape the intricate fabric of society. Yet, within these vast and multifaceted networks, it’s essential to acknowledge the paramount importance of the individual and their lived experiences. Our decision to focus primarily on individual trauma, as opposed to the broader categories of social or collective trauma, is rooted in our belief that the personal adversities and traumas an individual confronts play a significant role in shaping their identity and worldview.

These experiences, often painful and scarring, represent fragments of an individual, which when aggregated, paint a larger picture of a collective’s shared pain and resilience. It is our intention to unify these seemingly disconnected pieces, these remnants of our “broken” selves, to create a symbolic entity that represents our shared vulnerabilities and strengths. Through this endeavor, we aim to initiate a ceremonial observance—a funeral. This is not a mere event but a profound gesture dedicated to the collective mourning and acknowledgment of our fractured yet resilient identities, offering an avenue for healing and understanding.

From birth to death, individuals undergo significant transitions in social identity and status at various life stages. These transitions are often facilitated through culturally sanctioned “rites de passage”, as theorized by the anthropologist Van Gennep and expanded by Chappel and Coon, inventing the term “rites of identification”. According to their theories, rituals follow three fundamental stages: “separation”, “transition”, and “incorporation”. This means that individuals, as they progress through different stages of life or face significant milestones, temporarily separate from their existing social status and context. They enter an intermediary state during the transition phase until the completion of the ritual, officially marking the passage to a new life stage with a new social identity and status.

As a significant and “mysterious”, sometimes even unspeakable one among all rituals, we chose the form of funeral. It provides a structured space for grief, helping mourners process their loss and begin their journey towards healing. Funerals often serve to reaffirm cultural, communal, or religious beliefs about death, the afterlife, and the nature of existence. They offer a space for reflection and reconnection with these foundational beliefs. In general, trauma has always been a significant issue which people have to deal with. In addition, as the saying goes among the Han Chinese, “死生事大 (‘Si Sheng Shi Da’, The matters of life and death are of utmost importance).” In the multitude of life rituals, death represents the most profound transformation. Therefore, across cultures and throughout history, funeral rites have become the most esteemed rites of passage within the spectrum of life rituals.

As a significant and “mysterious”, sometimes even unspeakable one among all rituals, we chose the form of “funeral“.

As the saying goes among the Han Chinese, “死生事大 (‘Si Sheng Shi Da’, The matters of life and death are of utmost importance).”

Funerals serve as farewells, as commemorations, signifying the end of a person’s life. This ceremony is an act of paying homage to the deceased. In our course titled “Memory, Trauma, and Performance”, we comprehend that trauma often coexists with memory. Trauma never fully vanishes; instead, it reemerges in various forms, behaviors, and subconscious actions. Freud explored this phenomenon through his theory of “repeating” and “transference”; as for Van der Kolk, he argued that trauma can bring irreversible neurobiological harm to human brain, causing victims eternal wounds in mentality. These scholars composed thorough arguments about a variety of behavior or harm which trauma can bring, but what about the next step? How can people deal with, solve, or live with loss, to heal the wounds, to accept the scars? In this case, “rite de passage” offered a firm theoretical base for funerals to fulfill the above condition.

Death signifies the physical cessation of a person. However, the individual is never forgotten but commemorated uniquely. A poignant line from the film Coco encapsulates this idea, “When there’s no one left in the living world who remembers you… you disappear from this world. We call it ‘The Final Death’.” This suggests that a person’s death is only a physical end, while his or her spirit persists in diverse forms. Similar to how a song, an object, or a scent can evoke memories of the departed, these elements collectively contribute to the continued spiritual presence of the individual. In this sense, a strong correlation with the concept of trauma can be perceived.

The funeral was conducted in the traditional cultural Chinese style from the purpose of cultural exchange. As the only three students of East Asian descent, we aimed to introduce and share our traditional cultural practices with classmates from diverse national and continental backgrounds, allowing them to experience and immerse themselves in this unique cultural atmosphere. Moreover, it highlights the differences in how Eastern and Western cultures perceive death. Due to prolong influence from the famous saying “敬鬼神而遠之 (‘Jing Gui Shen Er Yuan Zhi’, Respect ghosts and gods and keep a distance)” by Confucius, death is often a taboo subject in East Asian culture, scarcely discussed openly due to beliefs that it brings bad luck or misfortune. However, it seems that death and funerals, though associated with sorrow and farewell, are generally accepted as part of life in the West. Thus, the idea of presenting such contrast by holding a ceremony that traditionally embodies avoidance to express a concept of acceptance came to life.

In conventional Han Chinese culture, there are a number of rituals marking different stages of the “death”, such as “the final moment (臨終, ‘Lin Zhong’)”, “the moment of death (新歿, ‘Xin Muo’)”, “the announcement of death (發喪, ‘Fa Sang’)”, “mourning rituals (殯禮, ‘Bin Li’)”, and the “burial (下葬, ‘Xia Zang’)”, most are private family affairs; however, there is one and only exception: the “farewell ceremony (告別式, ‘Gao Bie Shi’)“. The ceremony holds significant public importance as it symbolizes the departure of the deceased from society. It is usually held before the actual burial/cremation, where family members, friends and the other related bid their last goodbyes to the deceased, and it includes rituals such as family offerings, public offerings, and the funeral procession. It also involves various rituals and formalities to accompany the deceased on his/her final journey, reflecting universal aspects of human sentiment and societal customs.

In conclusion, our exploration into the intricacies of individual trauma within the broader context of societal rituals and funeral practices has illuminated the profound impact of personal experiences on shaping identities. By focusing on the individual as the locus of trauma and emphasizing the transformative power of funerals as a rite of passage, we sought to bridge cultural gaps and share the rich tapestry of East Asian funeral traditions with our diverse audience. The funeral ceremony, a culmination of various rites, serves not only as a farewell to the departed but also as a symbolic representation of shared vulnerabilities and strengths within our collective human experience. Through this ceremonial observance, we hope to foster understanding, healing, and acceptance of life’s inevitable transitions and losses.

II. Field Research and Preparation

Field Research 2023.11.02

Jean

On a warm, sunny autumn day, the three of us gathered at the entrance of the college, ready to embark on a field investigation in Chinatown. Where to go and what to explore? The funeral parlor. As we descended the steps into the subway station, I couldn’t help but wonder what my mother would react if I told her we had chosen “funeral” as the theme for our end-of-term project and were planning to visit a funeral home specifically. She would probably chase me around scolding me for making such an unconventional choice. From childhood, anytime we visited places related to life and death, like hospitals with mortuaries or temples with ossuaries, my mother would repeatedly caution us, insisting on wearing crystal bracelets obtained from Buddha, Bodhisattva, or other deities to ensure our safety and ward off any potential ghostly encounters.

However, on this day filled with sunlight, we deliberately sought out the shadows.

Despite considering myself an atheist, I confidently declared before the trip that I didn’t mind entering such liminal spaces, as long as I approached with respect for the departed souls. But, for my mother’s sake, I wore the bracelet and haven’t taken it off since. On the journey to the funeral parlor after exiting the subway, I remained self-assured. Yet, when we finally arrived, Jerrold, Ray, and I exchanged glances, unable to decide whether all three should enter together or if one should go alone. As I looked up at the black sign, despite all the mental preparation, why did my feet feel as if they were weighed down by a thousand pounds, making it impossible to climb those stairs?

After what felt like an agonizing eternity of restlessness and indecision, Jerrold volunteered to be the one to stride up the steps and open the door. He was our life savior.

The same scenario repeated itself in the second funeral parlor, with Jerrold taking note of the hall’s arrangement. Following this, we found a paper crafts shop, a tombstone store, and a Buddhist temple. We gathered mourning attire and incense, and planned to purchase a singing bowl, funeral attire, a photo frame for the memorial picture, and chrysanthemum online. After everything was settled, Jerrold and I headed to a Hong Kong-style restaurant for a belated lunch. In the midst of New York City, the search for fragments and clues related to Eastern death became a graduate student’s everyday routine, a diary entry, and preparation for a performance.

Preparation for the Funeral

Jean, Jerrold

The main character of the funeral must be the casket and the passed away it carries. However, in order to authenticate our plan of embodiment of the immersive funeral with the “East Asian/Oriental” aesthetics, we particularly did research about the items and customs of death rituals in our culture. The center spirit of all the items, rituals, and other factors of a typical funeral in East Asia is said to originate from an ancient book 禮記 (“Liji”), the Book of Rites/Courtesy, written more than one thousand years ago. It is a representative record of Confucianism, listing all the dos and don’ts for all types of ceremonies, including births, coming-of-ages, marriages, and funerals in ancient China. Especially when it comes to filial piety, as the saying of Confucius goes, “生,事之以禮;死,葬之以禮、祭之以禮 (‘Sheng, shi zhi yi li; si, zang zhi yi li, ji zhi yi li’, Treat (parents) with propriety in their lives; bury and memorialize (them) with propriety after their death)”, the “propriety” stems from inner grief or mourning, but instead of sentimental venting to the public, following certain manners in a ritual to “appropriately” express the emotions is what Confucius advocated.

The followings are the specific objects with meanings which we prepared for this project based on traditions:

Burning Incense

Burning incense is a custom inherited from ancient China. In the Chinese language, the phrase “burning incense” (「燒香」, “shao xiang”) phonetically resembles “sending a message” (「捎信」, “shao xin”), symbolizing the living conveying messages to deceased family members through the act of incense burning. This practice also incorporates expressions of remembrance and gratitude towards the departed loved ones.

We bought a pack of incense from a Buddhist temple and an incense burner at a ceramic shop in Chinatown, five dollars each. The pottery and porcelain merchandise in the latter was on sale, and we could not be more thankful for that. Furthermore, in most cases, there would be incense ashes poured into the burner for prayers to insert the incense sticks; but in our situation, we decided to replace it with rice. This is actually a common method for normal believers if they are worshipping deities at home.

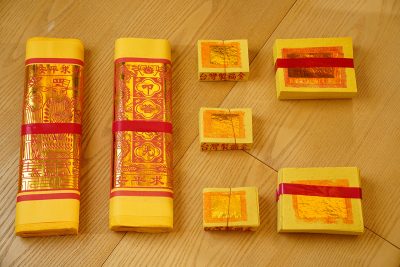

Joss Paper

Joss paper, or ghost money, believed by ancient people to be a universal currency for the deceased, is burned by the living as a means of sending money to the afterlife. According to ancient Chinese folk traditions, the souls of the deceased encounter numerous spirits obstructing their path to the underworld. Burning joss paper serves as a ritual to provide ‘road money’ for the departed souls, facilitating their passage by appeasing these spirits.

We decided not to put this in our cart out of budget and cleaning concerns.

Mourning Clothes/Dress/Garments

Wearing vests or robes made of ramie is the way to convey a sorrowful sentiment of not having the heart to dress up and expressing their deep mourning for the deceased. Normally, people wear different styles of mourning garments depending on how close they are with the deceased, for instance immediate family members wear hemp clothes, while relatives wear blue, and more distant relatives and friends wearing plain clothes.

On the other hand, in current Buddhist funerals in particular, immediate family members wear black robes.

This is the reason why we asked everyone to wear in the dress code of all-black/all-white.

Offerings

The purpose of offering sacrifices is to venerate, primarily signifying the acts of worship, commemoration, and adoration. Placing items in a specific location demonstrates one’s sincerity. Offerings typically consist of melons, fruits, cakes, alcoholic beverages, and other consumable food and drink items, encompassing both cooked and cold dishes.

The arrangement of these offerings also follows certain established guidelines. Generally, offerings should be placed in a clean and quiet environment, signifying respect for deities and ancestors. Moreover, the selection and arrangement of offerings vary according to different ceremonial occasions and festivals.

Food offerings: Food items are usually arranged on plates or in bowls to express reverence towards deities and ancestors.

Beverage offerings: Alcoholic and other beverage offerings are typically placed in cups or bottles, symbolizing devout respect for the deities.

Incense and candle offerings: Incense and candles are commonly arranged in incense burners or on candle holders, reflecting respect and awe for the divine.

In our funeral, aside from incense, we also prepared two kinds of the “五果 (‘Wu Guo’, five fruits with good meanings, which are orange, tangerine, banana, sugarcane, and apple), apple and tangerine. Apples are counted in four and tangerines in three respectively, put in the same number on both plates; the pronunciation of “four” resembles “death” in the Chinese language, but the number of three is blessed in Chinese culture. The Han people heavily value the meaning behind numbers, especially in the condition of rituals.

White Chrysanthemum

In Chinese culture, the chrysanthemum carries connotations of mourning and grief. The flowering of chrysanthemums in late autumn is associated with a sense of desolation and melancholy, making white chrysanthemums a common choice for expressing condolences at funerals. In East Asia, the color white has long been linked to sorrow, and the term ‘white affairs’ is commonly used to refer to funeral matters. Therefore, selecting a bouquet of white chrysanthemums after someone’s passing is an apt expression of sorrow and mourning, conveying a wish for the departed to leave this world in peace.

III. Arrangement of Ritual Context

1. Setup Arrangement

(1) Brief Description about the Background Screen

「奠」(“Dian”, Mourn/Mourning)

This Chinese character was specifically enlarged and put in the middle for important reasons. It is the representative character we use to describe ourselves “mourning” for someone/something. The “funeral” in Chinese culture that is open for people to come and mourn the deceased, or to be more precisely translated, the “ceremony for farewell (告別式, ‘Gao Bie Shi’)” , is also called “奠禮 (‘Dian Li’, The Ceremony for Mourning)”. This character is also often written on the wreaths given by people to the funeral as well.

輓聯 (“Wan Lian”, Couplet)

In Han Chinese culture, funeral couplets are a traditional means of expressing mourning. These are paired phrases commonly displayed on the lintel of funeral settings. The wording of these couplets usually includes praise for the deceased, expressions of longing, and comforting sentiments for the grieving family. It serves as a way to articulate respect and remembrance for the departed through the transformation of emotions into written words. They also play a crucial role in creating a solemn atmosphere, which is essential for comforting the emotions of family and friends. The serious and dignified language used contributes to the ritualistic ambiance of the entire funeral, establishing a reverent and composed atmosphere.

(2) The Collaged Photo (by Jerrold)

Diverse experiences of trauma shape people’s individuality and character. Thus, for the funeral portrait, partial facial features from each classmate were cut from their original photos and patched together, symbolizing parts of us – specifically, the aspects shaped by trauma. Therefore, the purpose of this funeral is to pay tribute to those parts of ourselves. Or perhaps, it seeks to find a way to coexist with our traumas.

2. Rehearsed Procedure

Entrance (Playing Each Memory a Message)

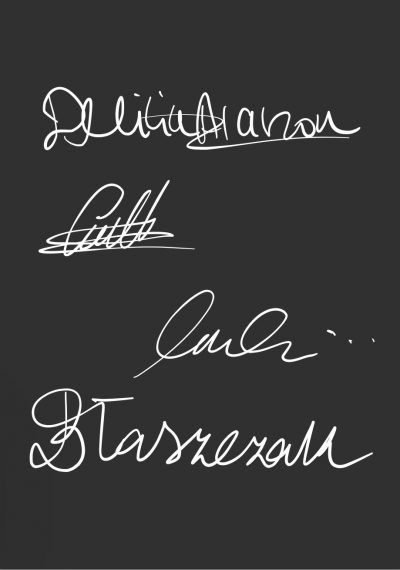

Jean – ask the participants to sign on the book and give three incense sticks

Jerrold – instruct participants put the incense to the burner, bow to them and give a flower per person

(Participants then get the flower and go to their seats. Wait until all people are settled.)

Opening – The Poem Recitation (Playing The Hug)

Jean, Jerrold, and Ray take turns reading every stanza of the poem.

Imagination Practice

Jean, “Now, you may pick a certain position that you feel comfortable with. You can sit, or find a place to lay on the ground. (Pause.) After getting ready, please close your eyes.”

(The instructions begin. Moreover, Jerrold will strike the singing bowl in the beginning of every paragraph.)

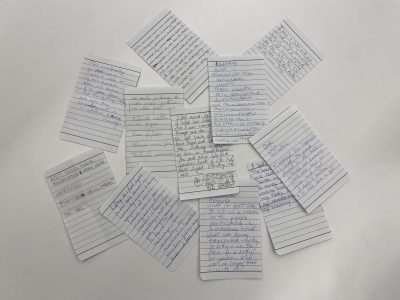

Writing After Practice

Jean, “Now, you may take the pen and paper under your chair. Spend five minutes write down what you saw, how you feel, or what you are thinking right now.”

(Pause.)

“After finish your writing, you may come to the casket and put the flower and your thoughts in it, then you may go back to your seat.”

Singing Session – Jiu Er

(Start without introduction)

Ending Words

Note: In the entire performance, Ray plays the role of photographer and recorder.

3. Music Choice

Jean

To clarify different stages and smoothen the progression of the Funeral, it was decided that three different pieces of music would be played successively to give a subtle hint. To begin with, the first song, Each Memory a Message by Evan Call, is one of the scores retrieved from an anime series Violet Evergarden, centering around the protagonist, Violet Evergarden, a former soldier who struggled to find her purpose and meaning in life after war. After becoming an “Auto Memory Doll” — a scribe who ghostwrites letters for others — she took on various writing assignments, encountering diverse people and experiences, gradually learning about emotions, empathy, loss, self-discovery and the power of words. Incorporating this song into our funeral performance creates a poignant and reflective atmosphere, allowing the fragments of self to be expressed through the emotional resonance of the music. Furthermore, the utilization of traditional Oriental instruments in this piece is also an essential factor for our choice.

The second is The Hug by Atli Örvarsson which was played through the opening of the funeral. This song was chosen mainly because of its soft and slightly grieving musical expression (in our opinion). However, after I searched the source of this song, it is actually also a film score from The Edge of Seventeen, a 2016 coming-of-age comedy. The theme of this film in fact can be said to show some connections with the purport of the recited poem, to offer a sorrowful but hopeful ambient. Even the title itself, The Hug, can convey the same warmness with its melodies.

Finally, the song performed by Jean at the ending of the funeral is “Jiu-Er (九兒)”, the theme song of the Chinese television drama series Red Sorghum (紅高粱, “Hong Gao Liang“) sung by Han, Hong (韓紅). This song consists of only four lines of lyrics. The first three lines vividly depict the abundant harvest and fragrant flowers in the countryside, creating an image of a bountiful and joyful autumn harvest. However, the final line alludes to a farewell, indicating that the singer, a girl named Jiu-er, is about to bid farewell to her beloved and may not meet again in this lifetime. The original meaning of the song is melancholic, as it reflects the sadness of parting with someone you care about. Yet, placing this song in the context of a farewell for a “fragment of self” imbues it with a different layer of meaning – “I am sending you off to a distant place, but I may not necessarily be sorrowful about not being able to see you again. Even on the day we reunite, whether with excitement or acceptance, you have shaped me, but I don’t necessarily have to carry you along with me.”

IV. Performance On-Day

(Scripted Content)

1. Before Entering

First, please sign here (on the signing book).

After signing, please take these three incense sticks and put them into the incense burner over there.

2. Opening

Ladies and gentlemen,

We gather here today not in the shadow of lost, but in the light of what has been. Today, we are here to honor and acknowledge a unique journey, the closing of a chapter, and the life story that we all share.

Thank you for being here today, for sharing in this moment of remembrance and transition.

In the quiet chambers of the soul,

where shadows dance and memories toll.

A funeral unfolds for fragments lost,

a eulogy for the self, at a heavy cost.

Mourn we do for the selves we shed,

in the garden of the heart, where they bled.

Whispers of yesteryears in the breeze,

as we lay to rest what no longer appease.

Each fragment, a chapter, a story told,

in the book of life, pages worn and old.

Yet, the funeral is not a dirge of despair,

but a hymn of rebirth, a breath of fresh air.

Gather ’round, those pieces let go,

bid farewell to the ghosts of long ago.

For in this mourning, a new dawn gleams,

a metamorphosis, beyond the realm of dreams.

The casket bears the weight of bygones,

as the mourners weep for battles won.

Yet, in the tear-stained tapestry of the past,

a mosaic of wisdom, strong and steadfast.

The procession moves through the corridors of time,

a symbolic farewell to the pantomime.

Of former selves, now laid to rest,

in the funeral for fragments, we are blessed.

So, let the funeral unfold with grace,

for fragments of self find a resting place.

In the sacred ground of self-discovery,

a funeral for fragments, a soul’s recovery.

3. Imagination Practice

Jerrold

Now, as you lay on the ground, relax your body as much as possible. Relax your shoulders, your arms, your hands, your legs. Let go of every piece of thoughts from your brain. You’re now in a cozy dark space.

In a cold and misty world, where a chill lingers in the air, you find yourself wandering. The atmosphere sends shivers down your spine as you traverse this enigmatic landscape. Walking forward, you stumble upon a firm, icy object. Instinctively, your hands reach out to touch it, feeling its cold and solid surface. You start to wipe it, again and again, each stroke gradually clearing away the frost and fog.

As the world around you slowly comes into focus, a startling discovery unfolds before your eyes. In front of you stands a tombstone, emerging like a sentinel from the mist. The inscription on the tombstone, previously obscured, now reveals itself, carrying a message from a time long passed.

Curiosity piqued, you lean closer to decipher the weathered script. The words, etched with care and reverence, speak of a life once lived, of dreams pursued, and of a legacy left behind. The name, though unfamiliar, resonates with a sense of history and stories untold. You stand in silent reflection, pondering the lives and stories that have slipped into the annals of time.

As you take in the scene, the world around you seems to transform. The coldness begins to recede, replaced by a sense of peace and introspection. The misty veil lifts, revealing a landscape rich with hidden memories and silent echoes of the past. In this moment of stillness, you feel a deep connection to the cycle of life and the timeless nature of our existence.

With a final glance at the tombstone, a symbol of both end and remembrance, you step back into the mist, carrying with you a newfound appreciation for the mysteries and wonders of life, and the quiet stories that lie in the most unexpected of places.

Now, you are getting away from this environment and starting waking up. You can try to open your eyes and look around. You have returned to this world that you are familiar with. Now, you can sit back in your seat.

4. Vocal Expression – 「九兒」”Jiu Er”

身邊的那片田野呀

Shen Bian De Na Pian Tian Ye Ya

手邊的棗花香

Sho Bian De Zao Hua Xiang

高粱熟來紅滿天

Gao Liang Sho Lai Hung Man Tian

九兒我 送你去遠方

Jiu Er Wo Song Ni Qu Yuan Fang

English Translation

Fields by side

Jujube flowers scent by hand

As the ripe sorghum red the sky

I, Jiu’er, bid you farewell and we may never reunite

5. Ending

As we gather here to bid farewell, let us remember that while we mourn the loss of our beloved us, we also celebrate the life they lived and the impact they had on each of us. In their journey, they touched our lives with love, laughter, and wisdom, leaving behind a legacy that will forever live in our hearts.

May we find comfort in our memories, strength in our shared sorrow, and solace in the knowledge that their spirit will always be with us. As we say goodbye, let us carry forward their light, honoring their memory through our actions and the love we share with others.

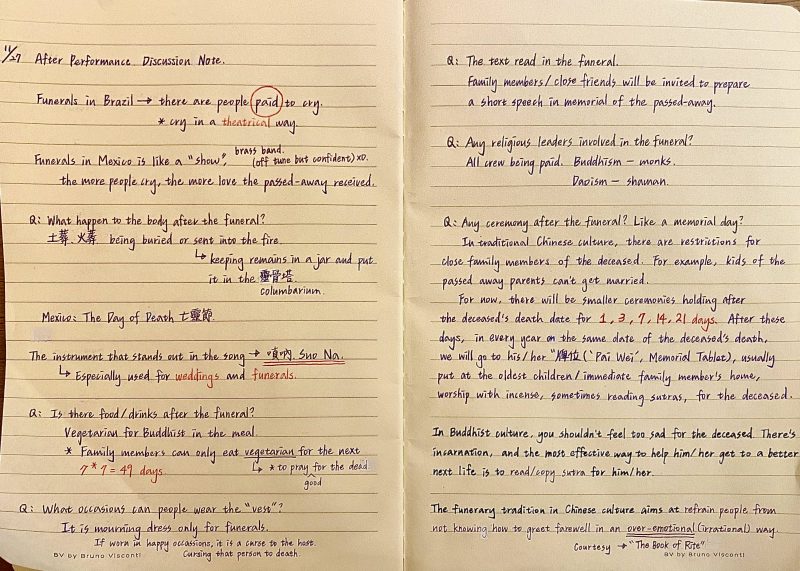

V. Discussion and Reflection After

From the Participants

Discussion Notes

Reflections from Team Members

Jean

The past few months of working on this project have been like a journey of steady progress with constant surprises. Initially, our idea was to create a collection of small works spanning different artistic mediums, including visual arts, music, and performing arts for a dynamic exhibition. However, the concept of a funeral emerged unexpectedly, and we found it intriguing to hold a ceremony that, in our culture, is seldom discussed despite East Asians being stereotypically perceived as having a “conservative and reserved” attitude towards significant life events.

From finalizing the theme to on-site inspections, procuring props, discussing ceremony details, preparing performances, venue decoration, to the final presentation, I never imagined that my first performance project could gradually take shape in such a beautiful and complete manner. It was also unexpected that a song I had practiced alone for several years would be chosen by the team to be sung to everyone. Initially, I felt quite anxious, comparing myself to Jerrold, who shared endless good ideas, and Ray, with his rich theater experience. What could I contribute with my background mainly in university essay research and writing? Fortunately, I excelled at asking questions, or what some may call “questioning.” While this trait can be annoying at times, I believe the questions I raised expedited the materialization of this performance.

I am grateful to my two team members, especially seeing them working hard and meticulously gluing cardboard for the coffin on the day of the performance; it truly made me feel that we all put a lot of effort into this project. I’m delighted that our participants enjoyed the performance and actively engaged in post-show discussions and sharing. This is a performance that has deeply impacted me and will likely be a story I share with friends and family for the next few decades.

Jerrold

Prior to this project, I wanted to give myself a funeral. However, this concept was perceived as inauspicious in the eyes of my parents. This raises a poignant question: why is it that the nature of one’s funeral, a deeply personal event, cannot be self-determined while alive, yet upon death, when one is devoid of agency, others are granted the liberty to shape it in potentially discordant ways? I want my funeral to be full of laughter, it doesn’t have to be anyone’s sad. I wish I could exist there and respectfully say farewell to the people around me.

In our endeavor, we sought to construct an environment conducive to introspection and collective contemplation, providing a platform where individuals could recognize and come to terms with the fragments of self lost through various life experiences. This initiative was anchored in the metaphorical representation of a funeral, symbolizing a profound process of acknowledging and honoring past traumas. Such recognition is not merely an act of remembrance but serves as a transformative journey, converting these experiences into reservoirs of strength and wisdom. This transformation is pivotal in the holistic development of the individual, as it fosters resilience and a deeper understanding of the self within the broader tapestry of human experience.

“Construction” – Ray

As the Oriental culture of funerals, we found some funeral shops to research the form of the funeral from the coffin preparation to mourning dresses. We went to a tombstone company to find the mourning dresses. After research, we learned how to create a real funeral event. We decided on the form of the coffin, a combination of two benches, using the cardboard to fix it, and then putting the cloth on the cardboard.

We want to enroll the Oriental culture of funerals in the Western world. It would be a supplement to the Memory, Trauma, and Performance class and also the cultural fusion. People all around the world (classmates who came from different parts of the world) will get a sense of the mourning methods when people die and how Asian people heal their close relatives. When we made this idea the project, we met twice each week to discuss the details of the funeral, such as the timeline and the props. When the props should reach and when the technical rehearsal would have happened. During Thanksgiving week, we could notuse the rehearsal room, so we decided the technical rehearsal would happen on the day of our performance.

As I did have the experience of ensemble work before, the principle of ensemble is one plus one greater than three. Thus, the participants should base the ideas on the first person and add a layer to those ideas. Then, the group runs in the cycle to create the projects. As Stanislavski mentioned, “Teamwork, which is the basis of our acting here, calls for an ensemble, and anyone who disrupts it is guilty of a crime not only against his colleagues but against the art he serves” (Konstantin Stanislavsky 2008, p. 564). In this collaborative project, Jerrold came up with the idea of the funeral to respond to the course for the practice. We helped each other to generate ideas and to construct the project. In this project, we would like to illustrate how people repair after someone dies around them. Hirschmentioned, “Memory signals an affective link to the past—a sense, precisely, of a material ‘living connection’—and it is powerfully mediated by technologies like literature, photography, and testimony” (Hirsch 2012, p. 33). The funeral of performance lets people recall and recover in memory of that person.

For the construction of the work, we chose different materials to make the coffin, which used the two benches knocked togetherand the reversal of the benches top faced the ground as a foundation, we put the cardboard around the benches and used the packaging tape to fix the object. After we put the cardboard above the beam of the benches as an inner space for the coffin. In the last step of the coffin, we put the cloth on the model. Before we also thought of using a big cardboard to mimic a coffin, but the real issue was that the big cardboard was not suitable for the installation itself to support the stuff above the installation.

Bibliography

Anzaldúa, G. E. (2015.) Light in the Dark. Durham and London: Duke University Press. p.10

Baumrind, D. (1971.) Current Patterns of Parental Authority. Developmental Psychology Vol. 4. No. 1.

Chan, S. (1986.) Parents of Exceptional Asian Children. Exceptional Asian Children And Youth. Edited by Kitano M., Philip C. Chinn. United States: The Council for Exceptional Children. p.41-42

Cheng, Z. M. (2007.) 第四章:稱情立文的喪禮文化 (“Di Si Zhang: Cheng Qing Li Wen De Sang Li Wun Hua”, The funeral culture that expresses emotions through eloquent words). 殯葬文化學 (“Bin Zang Wun Hua Xue”, Studies of Funerary Culture). 國立空大 (“Guo Li Kong Da”, National Open University).

Chung, S. K., and Li, D. (2017.) An Artistic and Spiritual Exploration of Chinese Joss Paper. Art Education. p.70

Cormack, A. (1927.) Funeral Preparations. Chinese Birthday, Wedding, Funeral, and other Customs. China: China Booksellers. p.62-75.

Freud, S. (1924.) Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through. Further Recommendations in the Technique of Psychoanalysis: Recollection, Repetition, and Working Through. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis. p.147-155.

Hirsch, M. (2012.) The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press.

Liang, Y. D. (2015.) 先秦儒家宗教性研究──以孔孟荀對「喪 葬」、「祭祀」、「天」的觀點為討論中心 (“Xian Qin Ru Jia Zong Jiao Xing Yan Jiu – Yi Kong Meng Xun Dui ‘Sang Zang’, ‘Ji Su’, ‘Tian’ De Guan Dian Wei Tao Lun Zhong Xin”, Research on the Religious Aspects of Pre-Qin Confucianism – A Discussion Centered on the Views of Confucius, Mencius, and Xunzi on ‘Funeral,’ ‘Burial,’ ‘Sacrifice,’ and ‘Heaven.) National Cheng Chi University. Phd Dissertation.

Kemske, B. (2021.) Crack Made Whole in a Golden Repair. Kintsugi: The Poetic Mend. London: Herbert Press. p.12-17

Konstantin S. (2008.) An Actor’s Work. London; New York: Routledge.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014.) Running for Your Life: The Anatomy of Survival. The Body Keeps the Score : Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma. The Penguin Group.

Xie, Z. R., Li, X. E. (2017.) 陪死者走最後一程──台灣喪葬禮俗大解析 (“Pei Si Zhe Zo Zui Ho Yi Cheng – Tai Wan Sang Zang Li Su Da Jie Xi”, Accompanying the Deceased on Their Final Journey: A Comprehensive Analysis of Funeral Customs in Taiwan). 獨立評論 (“Du Li Ping Lun”, Independent Criticism). Retrieved Dec 8, 2023 from https://opinion.cw.com.tw/blog/profile/374/article/5818.

Xie, Z. R., Li, X. E. (2017.) 生命告別為何隆重:解析台灣喪葬禮俗 (“Sheng Ming Gao Bie Wei He Long Zhong: Jie Xi Tai Wan Sang Zang Li Su”, The Grandeur of Farewell to Life: Analyzing Taiwanese Funeral Customs). The News Lens. Retrieved Dec 8, 2023 from https://www.thenewslens.com/article/71891/fullpage.

Yagi, D. K. (1995.) Protestant Perspectives on Ancestor Worship in Japanese Buddhism: The Funeral and the Buddhist Altar. Buddhist-Christian Studies. p.15

Yao, X. Z. (1994.) Chinese Religions. Rites of Passage. Edited by Holm, J., Bowker, J. London, New York: Pinter Publishers. p.157-167

VI. Work Allocation

Jean Huang–

Topic Discussion, Prop Purchase, Host and Singer of the Day, Presentation, Chapter Writer, Main Chapter Editor

Jerrold Poon–

Topic Discussion, Idea Provider, Setup Designer, Performance Arrangement, Video Editor, Presentation, Chapter Writer

Ray Yang–

Topic Discussion, Setup Maker, Invitation Writer, Photographer and Recorder of the Day, Chapter Writer

Xinzhong, Yao. 1994. "Chinese Religions" Rites of Passage. Edited by Jean Holm, and John Bowker. 157-167. London, New York: Pinter Publishers, Xie, Zong Rong, and Xiu Er Li. 2017. "生命告別為何隆重:解析台灣喪葬禮俗 ("Sheng Ming Gao Bie Wei He Long Zhong: Jie Xi Tai Wan Sang Zang Li Su", The Grandeur of Farewell to Life: Analyzing Taiwanese Funeral Customs)." The News Lens., 8 Dec 2023. https://www.thenewslens.com/article/71891/fullpage. Cheng, Zhi-Ming. 2007. "第四章:稱情立文的喪禮文化 ("Di Si Zhang: Cheng Qing Li Wen De Sang Li Wun Hua", The funeral culture that expresses emotions through eloquent words)" 殯葬文化學 ("Bin Zang Wun Hua Xue", Studies of Funerary Culture). 11. Taipei, Taiwan.: Place of Publication 國立空大 ("Guo Li Kong Da", National Open University), Xie, Zong-Rong, and Xiu-Er Li. 2017. "陪死者走最後一程──台灣喪葬禮俗大解析 ("Pei Si Zhe Zo Zui Ho Yi Cheng – Tai Wan Sang Zang Li Su Da Jie Xi", Accompanying the Deceased on Their Final Journey: A Comprehensive Analysis of Funeral Customs in Taiwan)." 獨立評論 ("Du Li Ping Lun", Independent Criticism), 8 Dec 2023. https://opinion.cw.com.tw/blog/profile/374/article/5818. Cormack, Annie. "Funeral Preparations" Chinese Birthday, Wedding, Funeral, and other Customs. 62-75. China: China Booksellers, 1927. Chung, Sheng Kuan, and Dan Li. "An Artistic and Spiritual Exploration of Chinese Joss Paper." Art Education 70. 2017. Accessed 7 Dec 2023. Yagi, Dickson Kazuo. "Protestant Perspectives on Ancestor Worship in Japanese Buddhism: The Funeral and the Buddhist Altar." Buddhist-Christian Studies 15. 1995. Accessed 7 Dec 2023. Baumrind, Diana. "Current patterns of parental authority." Developmental Psychology 4. no. 1: 1971. Accessed 23 Dec 2023. van der Kolk, Bessel A.. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score : Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books, Kemske, Bonnie. 2021. "Crack Made Whole in a Golden Repair" Kintsugi: The Poetic Mend. 12-17. London: Herbert Press, Freud, Sigmund. "Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through" Further Recommendations in the Technique of Psychoanalysis: Recollection, Repetition, and Working Through. 147-155. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1924. Anzaldúa, Glória E.. 2015. Light in the Dark. Durham and London: Duke University Press,