Traumas are immeasurable, but they can be felt throughout the body. In this chapter, we aim to discuss trauma reflected in three different mirrors. Kulshreshtha’s performance looks at the experience of trauma itself, depicting it as something embodied instead of archival, using the case of presenting in a court of law. Thorne’s contribution looks at how we can think with trauma as a means, not only of survival, but as a means of rethinking justice. In Silva’s story, trauma appears to approach cigano (1) identity, specifically those families who hid their ethnicity to assume a white identity to survive.

Performance of a Sales Pitch

In “Remembering the Past”, Caruth defines trauma as something that “does not simply serve as record of the past but precisely registers the force of an experience that is not yet fully owned” (Caruth, 151). Her writing talks about accident victims forming “waking memory” that is “returned, repeatedly, only in the form of a dream” and a flashback as “having no place” either in the past, where it was not fully experienced, or the present, where it is not fully understood (Caruth, 162-163). Caruth explains the impossibility of trauma’s translation into working memory as a point of departure from it, taking the example of Claude Lanzmann’s film on Holocaust testimonies, Shoah. She poses the question: how do we begin with impossibility? Van der Kolk also looks at how “our stories change and are constantly revised and updated” (Van der Kolk, 209) – he takes the case of legislation and the problem with autobiographical memory being imprecise. He talks about the problem with associating adrenaline secretion as a way for precision, linking it to the confrontation with the horror of “inescapable shock”; how the system becomes overwhelmed and breaks down (Van der Kolk, 211). He talks about the fragmentation of memory. Hermon lists hyperarousal and combat neurosis as symptoms of trauma, and overcoming trauma-induced fear as reenactments of the original and taking risks – “Yet part of me feels that if I don’t walk there, then they’ll have gotten me. And so, even more than other people, I will walk up that lane” (Hermon, 29). In a contained setting, these reenactments can be socially useful. The choreography of the body itself varies from culture to culture, shifting and connoting different things – Connerton discusses such practices and how the choreography of the body can portray authority in different cultures. On the topic of institutionalization of performance, Connerton writes, “When the memories of a culture begin to be transmitted mainly by the reproduction of their inscriptions rather than by ‘live’ tellings, improvisation becomes increasingly difficult and innovation is institutionalised” (Connerton, 75). One has to become akin to a professional actor in order to present their own story in a court of law. Diana Taylor demonstrates how trauma studies and performance studies remain linked to one another, as well as how trauma and narrative — especially through live tellings and performances — remain linked: “The transmission of traumatic experience more closely resembles ‘‘contagion’’: one ‘‘catches’’ and embodies the burden, pain, and responsibility of past behaviors/events” (Taylor, 168); the subject in this sense suffers. Taylor demonstrates how trauma lives in the body, not in the archive – on the subject of disappearances, live performances, and archiving performance, she writes: “The live can never be contained in the archive; the archive endures beyond the limits of the live” (Taylor, 173).

In the studies of the performance of everyday life, any performer performing an act is said to be “not, not me” while in the act. Through the revisiting of a personal trauma, one is put in the same position all over again. If it’s not for the purpose of healing (or one has not healed beforehand), presenting in a court of law can be doubly traumatic. The performance goes to demonstrate ideas of docile bodies, the means of correct training, and panopticism from Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, with the idea of the choreography of the performance as it would be presented in a court of law itself broken down further, taking a satirical, provocative turn.

In my research, I looked at three cases of legislative theatre: The case of the Johny Depp and Amber Heard trial and its snippets on social media, and its presentation in a subsequent documentary; ‘Prima Facie,’ a one-woman play that was performed on Broadway starring Jodie Comer, the popular star of the hit Hulu show ‘Killing Eve’ depicting the story of a survivor (see below for a marked quote that depicts the cultural significance of the story); and Kaitlyn Jorgensen, a public figure that offers support to survivors of assault and mothers through her workshop on Ingram. In the case of the recent Johnny Depp and Amber Heard trial, the fact that the recordings were broadcast live on social media and through Instagram’s algorithms from an already biased perspective creates this whole other problem of taking hold of and shifting mass culture in a way that serves Depp, given his fame and reputation. In the end, the entire thing is a shameful and unfortunate thing, with the doubly humiliating role that Amber Heard is put in (also with the making of the subsequent documentary — movements like #MeToo can be weaponized and turned on themselves through a patriarchal lens). ‘Prima Facie,’ a one-woman play that stars Jodie Comer on Broadway, looks at a criminal defense barrister whose view of the legal system changes after she is sexually assaulted. The play is powerful in the way Comer depicts the experience of rape itself and channels feelings toward the rape perpetrator, addressing the audience in a deeply moving way. It demonstrates how sexual assault is not a linear, scientific story, but a violation of someone’s body that affects the person’s physical, psyche, and soul. All the cases go to show that trauma is not something scientific, measurable, or calculable in a court of law, but is a deeply viscerally felt experience — with its performance requiring some level of choreography, whether presented in a classroom, a workshop, or a court of law.

Purely from a fan perspective, it’s safe to say that later seasons weren’t received as warmly as the first two, so there’s definitely a sense that now is the right time to bring “Villaneve’s” story to a close. In fact, some fans even breathed a sigh of relief when the announcement was made, precisely for that reason.

by Shreya Kulshreshtha

Trauma beyond a sentimental model of justice:

‘What if

my own being

broken

is the new law’

We are here to slow time, Simon White

Bessel van der Kolk in The Body Keeps the Score breaks down some of the key functions of trauma. He views trauma and PTSD as working with FRAGMENTS stating trauma is primarily remembered not as a story, a narrative with a beginning, middle and end, but as isolated SENSORY imprints: images, sounds, and physical sensations’ (p.70). Van Der Kolk also makes the observation that traumatic memory differs from normal memory in that it PRESERVE accounts. He states ‘whether we remember a particular event at all, and how accurate our memories of it are, largely depends on how personally meaningful it was and how emotional we felt about it at the time. The key factor if our arousal. (p.177)’

I have found Frida Orupabo’s collages interesting to think through in relation to trauma. Frida Orupabo’s collages are of cut up black bodies. These works Gail Lewis notes refer to the degendered ‘public skinning of black women’s subjectivities’ that remove the capacity for feeling. So, in many ways they return blackness to the traumatic scene of subjugation. The cut-up images that place eyes, hands, and feet in places they should not be, are rich in textures and colours, which induce a tingling, of affect. Methodologically then these images invoke the fragmented, sensory and preserving logic of trauma Bessel Van Der Kolk defines.

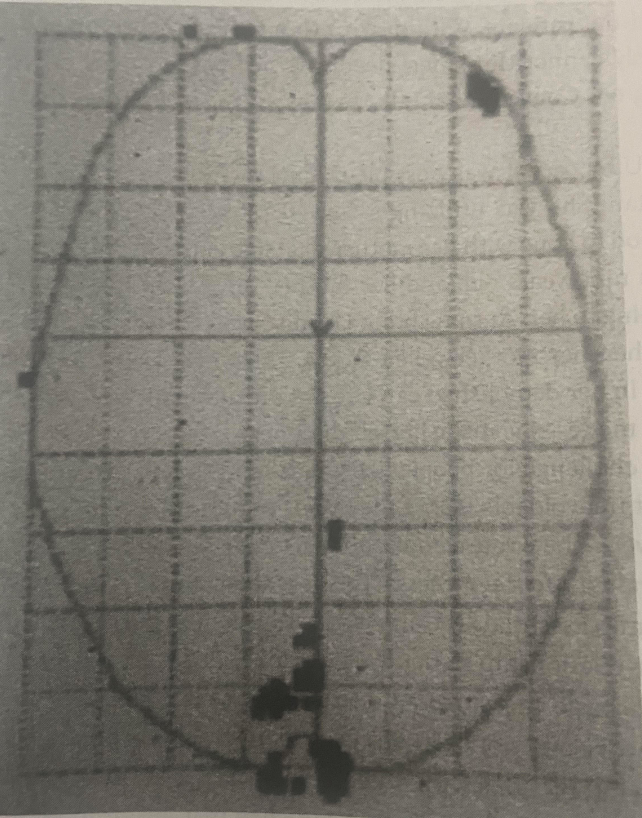

One of Bessel Van Der Kolk’s key claims is to demonstrate how trauma can cause the brain structures to desert us. In the Image below it is made clear that the brains responses have been blanked out when reminded of past trauma.

Van Der Kolk tells us the medical term for this response is depersonalization. Throughout The Body Keeps the Score Van Der Kolk stresses the importance of mending this state of unfeeling. Where standard theory does this by desensitising the traumatised through gradual exposer Van Der Kolk proposes repair through presents stating ‘we must most of all help our patients to live fully and securely in the present….if you cannot feel satisfaction in the ordinary everyday things like taking a walk, cooking a meal, or playing with your kids, life will pass you by’ (p.73).

This is where I believe Frida Orupabo’s collages can teach us something different about trauma. Frida Orupabo presents us with ‘unfeeling’ figures stripped of the capacity for feeling. Expressionless images taken from achieves, that remind us of Tina Campt’s, Listening to Images. Instead of looking at these quiet documentary photographs, Campt and Orupabo listens to them, detecting in them the hum of refusal in small gestures of anticolonialist defiance and difference. Orupabo collages are trauma informed in that they are careful not to reproduce, trigger trauma, yet they don’t simply aim to fix trauma either. I would argue that they work creatively with the unfeeling of trauma, taking the reality of love, grief, and pain seriously.

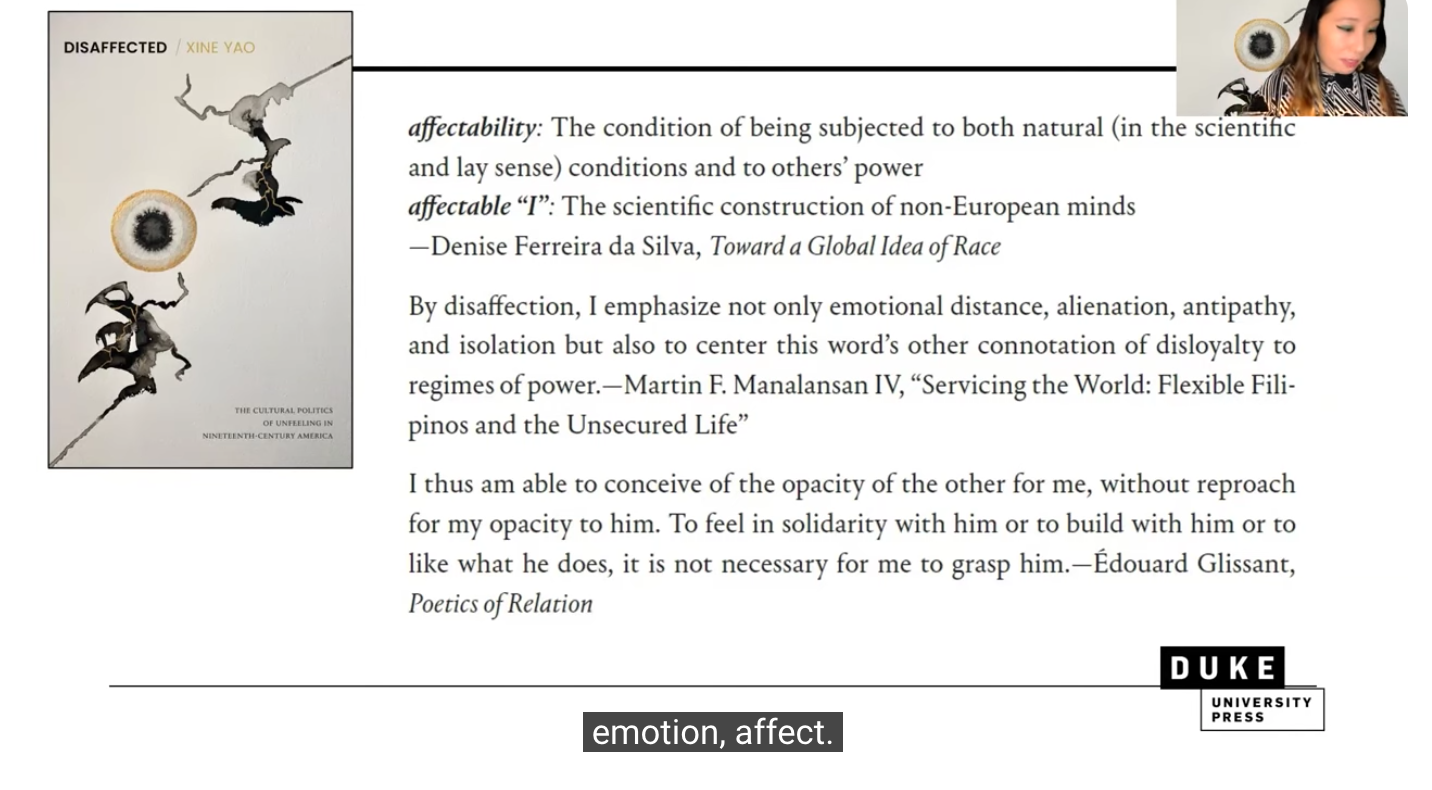

For Xine Yao, ‘unfeeling’ is an important means of survival and refusal of universal feeling. Xine Yao’s ‘theory in the flesh’ references Denise Ferreira da Silva’s who see’s universal affect as leading to Enlightenment’s universal “Man”. In the work of Frida Orupabo’s we see how explorations outside of the bounds of the designed human might be a means of responding to affect’s universal “Man”, offering an emancipatory existence outside of the crushing and violent paradigms that trap them.

These ‘unfeeling’ figures I argue act as an example of ‘disaffect’, asking us to abandon our reliance on routines of performance that permit us to be seen and known by others. Resisting majoritarian feelings and the liberal politics of recognition, feeling otherwise opens new ways to talk, among ourselves.

Listening to Images Workshop

Inspired by Frida Orupabo’s collages and Augusto’s Boal’s Theatre of the oppressed I designed a workshop for my group to.

Theatre of the Oppressed explicitly deals with language. It started as part of a literacy campaign called ‘Operacion Alfabetizacion’ in which the government in Peru aimed to ‘eradicate illiteracy with the span of four years.’ To create a poetics of the oppressed the ‘spectator’ must be turned into ‘subjects’ or ‘actors.’ Boal distinguishes this method from Aristotle and Brecht’s poetics with the assertion this is not catharsis or critical consciousness but action itself where ‘the liberated spectator, as a whole person, launches into action’. What is key to this method for me is that it is creating dialogue, language, and expression that is embodied by giving the ‘means of production’ to the people, letting them start from what they already know and use language built on that, to better understand their stories, and what they already know. It is in the process of making language that knowledge is realised. Meaning is demonstration-like, a staged act of speaking and reading rather than the effect of emotional peaks and troughs or mimesis.

Theatre of the oppressed is normally built around a pedagogy of hope, however, for this project I am using the idea of futurity rather than hope. Futurity is a concept in the work of Tina Campt that refers to a practice of making the future in the present. I have brought this concept in to replace hope as although both start with a situation of oppression that must be overcome futurity brings with it the possibility to talk about refusal and survival.

Augusto’s Boal has a technique that uses photography called photo-romance. This involves interpreting photographic narratives through re-enactment and then requires a conversation around the interpretation. My collage workshop asks participants to interpret as they go. Building outwards from the smallest details, avoiding the process of naming, ownership, and subjection. Collage as a medium allows us to touch another temporal zone.

To start I made mulled cider, an achieve of black and white images, and a stage.

Listening to Images

1. Treat your paper like a stage.

2. Analysis your performance scene:

Where is the power?

Where is the trauma?

What would be the ideal situation?

How can we create this scene differently?

What creative response to trauma could we use?

3. Highlight parts of the body we need to activate, try repeating them?

What do we want to connect to what? Draw lines?

What needs shutting down? Cut it out, fill it in?

Take notes of your process.

This is more about the process and conversations than the final image.

Reflection on process:

I had feedback that the set of instructions felt to abstract for one participant. As Boal suggests I tried not to be involved as the facilitator, but I had to break down the prompts for action into more direct calls.

I am also aware my workshop heavily relied on us being able to talk the same language and having been in this class together so a shared understanding to a degree. However, it was still interesting how differently we understood things.

Parts of the final collage:

By Chloe Thorne

Dance for Your Supper

Brazilian background

To live in poetry. A colleague, cigano from the Kalon family, says that it’s a way of living. I agree. This cultural understanding as a way of seeing life is part of the filosofia cigana (roma philosophy), which can only be known by listening to music and in conversations with families, almost as a “popular knowledge” that everyone knows—everyone who knows us.

Being a cigana in Brazil is different from being one in Europe in general. Since I was a little child, growing up in São Paulo (in the southeast of Brazil, the country’s largest city in terms of population), I have known there is a romanticized imaginary scenario about ciganos, endorsed by mainstream media, including the most powerful and viewed channel producing long soap operas about ciganos, like Travessia (2022), Explode coração (1995), Pedra sobre pedra (1992), among others. For instance, it is very common in urban cities to have “cigana dance classes” given by gadjos (2). Besides, the college dance courses offer cigana dance as part of the curriculum, usually focusing on folklore or regional dances. Even though the visibility of a stereotypical image of the cigana culture is inserted in non-ciganos’ life, the myths of “ciganos are thieves” or “ciganas will kidnap your child” are frequently used as background for the violence that nomadic ciganas continue to endure. A certain visibility is not synonymous with social acceptance, and this kind of visibility, also hasn’t led to thinking politically about the issues of the community.

In regards to public policies, it would be a fallacy to state that they aren’t improving. Public health directly affects the majority of the ciganos, not only because the financially poor families don’t have access to it but also because they struggle culturally with Western medicine in many aspects. Research and specialized booklets and journals have been produced by several branches of the Ministry of Health and other Ministries, such as Culture, Education, and Racial Equality, in order to educate health professionals to understand cigana culture, diminish structural racism, or demystify prejudices that are barriers to the access of the cigana population (Brasil, Subsídio para cuidados 6; Silva Júnior 264). These studies are made by both ciganos organizations, such as Associação Internacional Maylê Santa Sara Kali, and non-ciganos in order to achieve comprehension in all stages.

Addressing public safety is a bigger problem. In 2022, the Estatuto Cigano [Roma Bylaw] was approved by the Brazilian government with the statement of guaranteeing safety and equality to all the cigano population (Senado Federal, “Estatuto dos povos ciganos”). This document is important because it opens a precedent to fight legally for land, against police oppression and other violence faster due to its typification.

There isn’t much academic literature on refugee flows of the nomadic population to Brazil, as well as the reasons for violence against this population, but it is a common agreement that loads of cigano families lied about their own identity in order to survive and others have changed a lot of their own culture in order to be adapted to a new gadjo environment (Silva Júnior 421). On the other hand, after the enslavement period in Brazil in 1888, the colonial legacy of enslaving, raping, and murdering indigenous and black populations left a multiracial identity—not biracial—, where “there was no clear-cut racial line, either legally or in social practice” (Skidmore 5). Brazilian politics, therefore, were followed by several temptations in many parts of the country towards whitening (branqueamento, in Brazilian Portuguese) the entire population, including bringing peasants from Europe and redistributing some lands in order to have cheap labor to substitute the black slaveries—it is important to highlight that there wasn’t any kind of reparation or public policy for the black and indigenous population after the enslavement period, concentrating the little redistribution of land over the European community (Skidmore 8).

During the 19th century, ciganos immigrated to Brazil along with European non-ciganos. A great group of Germans, Italians, Poland, and Russians arrived. Ciganos from Yugoslavia lived in Rio Grande do Sul, Bahia, Pará and Pernambuco; Romanians went to São Paulo; Greeks to São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. However, in all the states mentioned there were even more nationalities in minor groups, such as from Albania, Serbia, Poland, Russia, Bulgaria, and Hungary (Goldfarb et al 298; China 299). Throughout the 1930s, another group of Italians immigrated as well, running away from the Nazi-Fascism and the World War II. A significant portion of the group of ciganos who arrived in this country could use their whiteness as racial privilege if they hid they were ciganos in order to survive. Some of them did. And that is our starting point.

Thinking about those contrasting situations, this piece aims to elaborate on the remains of hiding the cigana identity in order to survive and how it can affect the population through generations. To achieve it, we discuss Judith Herman’s works in relation to cigano documents and Brazilian politics, as well Bessel van der Kolk’s and O’Neills’s studies about intergenerational transmission of traumatic upheaval, investigating the relation through performance as healing and acknowledgment tool, a step to seek accountability and justice.

Truth(s)

Heritage is a weighty word. When a family arrives in a new country without any support (financial, social, cultural, or political) and chooses, even if unconsciously, to hide their ethnicity because they feel they might fit in easier, what are the consequences? On the other side, how do cigano families nowadays endure their own heritage after all those years of violence? Could culture work as a weapon for surviving, or could it be lost in memories?

When Judith Herman explains in her book Truth and Repair about tyranny and how its agency works, she writes that

it is necessary to break the victim’s spirit. Three additional methods are required. The first is isolation, fracturing relationships with others who might offer solace and support. Batterers, for example, may demand that their partners stop visiting their friends and families, often with jealous accusations of infidelity. The second method is degradation, dirtying the victim so that she will feel repulsive to herself and to others and forcing her to do things that she finds humiliating and disgusting. The last and most toxic method of all is forcing the victim to violate her own moral codes by betraying or harming those she loves. These last three methods work primarily by inducing not fear but rather shame. (28)

This example is very sophisticated and may be used not just in the person-to-person approaches that she mentioned; it also works as a foundation for an entire race or ethnicity to see its own identity structurally. If you think of a refugee family in a new country with a whole new cultural environment, it is possible to apply these three steps. First, isolating families from each other in small groups or denying basic survival (such as jobs, land, or health); second, isolating them culturally, endorsing racism in all categories, corroborating myths about different cultures by demonizing or dehumanizing non-Christians; and third, making them ashamed of who they are. If we add to the big picture, as introduced, the government interest in whitening the Brazilian population by bringing the Europeans and the Nazi-Fascism fear atmosphere of the Second War, choosing to live by taking advantage of the racism in this new country and embracing the identity that banished or mistreated them in the first place may be the only way to survive. What is the cost, though? “Shame, like fear, is an intense emotion that creates indelible memories” (Herman 29).

The choice of living as white gadjos drives us to reflect on the population that cannot invent a new narrative to live in because they don’t have the white component. In Plantations Memories, talking about the reality of black women, Grada Kilomba traces a comparison with Simone de Beauvoir’s idea that the woman is the Otherness (woman is the other of the man). She goes further in the analysis, saying that white women may oscillate between privileges, while black women are the other of the other:

Being neither white nor men, Black women come to occupy a very difficult position within white supremacist patriarchal society. We represent a kind of a double lack, a double Otherness, as we are the antithesis of both whiteness and masculinity. In this schema, the Black woman can only be the ‘Other,’ and never the Self. (117)

For ciganos who have hidden their identities, the privilege of passing as white may leave a scar of shame through generations, even though it is also, at the same time, responsible for saving their lives.

If we follow Herman’s logic, families who hide their identity could become bystanders of their own culture, of the identity they chose to leave behind, as they “gain the benefits of active collusion in a corrupt system; they can become silent witnesses who are aware of abuses of power but keep quiet out of fear or indifference; or they can simply retreat into a stance of unknowing, feeling that they are powerless to make a difference in any event” (31). When the tyranny strategy is introjected in the veins of white cigano families, i.e., assuming a white identity and being ashamed of who they are, the full circle of the whitening population is complete.

Roots and performance

I am pretty sure that being alive isn’t enough. When performing a dance, I am able to feel my whole body moving; I am intensely present. Moreover, I am entirely committed to the present. The acknowledgement of a past influences actions; afterwards, one cannot choose to unknow something one already knows.

Official and non-official research mention that there are from 650 thousand to 1.2 million ciganos in Brazil, constituting a very plural ethnic group (Goldfarb, 427). Taking into account all the families who have hidden their identities, this number increases. Looking at those numbers, addressing individually what this loss of identity might inflict on someone seems impossible, but understanding that the coercion of tyranny can leave deep wounds, individual and collective, may offer us some elaboration on collective trauma.

These wounds are part of the social ecology of violence, in which crimes against subordinated and marginalized people are rationalized, tolerated, or rendered invisible. If trauma originates in a fundamental injustice, then full healing must require repair through some measure of justice from the larger community. (Herman 9)

The complexity of choices, since the arrival of different cigano nationalities in Brazil, summing up the racism against non-colonial cultures and people, the dangerous conditions of living for financially poor people, the traumas that the families already carried due to the Second World War and other very violent regimes, juxtaposed with the advantage of performing whiteness, show how entangled and deep the ethnic cleansing is.

But if hiding is an option, remembering is intrinsic to it. First, the distortion inflicted by making a person ashamed of her/himself, individually or structurally, doesn’t make an identity vanish because traumatic memories can be triggered. Collectively, groups that suffered a very traumatic experience could pass it on genetically through generations.

Families who generations ago experienced traumatic upheaval resulting from war, residential schooling, oppression and racism, natural disasters and other events, may experience various effects and enactments of the trauma passed on from parent to child. Transmission is considered to be unintentional, and often without awareness of the contribution of the original traumatic event. (O’Neill 173)

In this way, daughters and sons of this trauma could carry the symptoms with them. However, there are studies that delimit generational trauma to the third generation. O’Neill’s investigation highlights that there are “examples of symptoms in the third generation which are linked to hidden trauma two generations earlier, symptoms that are seemingly resistant to change in individual therapy, suggesting to the authors an epigenetic contribution” (181). This study lights a path to thinking about whether this sutured part of identity bars the ability to feel entirely alive too. According to Van der Kolk, in an experiment brain-scanning traumatized victims (not intergenerational victims), it presented “an effort to shut off terrifying sensations, they also deadened their capacity to feel fully alive” (115). Naturally, it isn’t evidence enough, but thinking through my own family, it fits perfectly.

(First) Final Considerations

Joy, I tend to believe, is a weapon against trauma. Thus, it leads us to the first sentence: live in poetry. This deep-rooted filosofia cigana isn’t about looking to the bright side of life; it is about being fully alive and refusing to live based just on surviving. If you can write poetry, then you are able to create. Creating is owning your own agency, a narrative using your own voice. Evoking a dialogue during a lecture in Albertine Dance Season (2023), between Ruth Estevez (an independent curator from New York) and Professor André Lepecki (NYU), when she asks if “performance could give a second chance to history,” Lepecki answers that “just being fully engaged with the present, we may give history a second chance.”

In this way, performance can not only heal, but also incarnate a reality, a true commitment to the present. As a weapon, performance could be used for different purposes. It might heal the person who embodies a performance, in this case a dance; the performance also carries the power of transmitting the traumatic memory. This acknowledgement, therefore, is about responsibility too. “Caring acknowledges the interconnectedness between ourselves and others, ourselves as only a part of that larger entity” (Taylor 122).

Although I believe the concept of reparation is very subjective to each person, when the topic concerns collective trauma or (un)hidden memories, not only is the joy unveiled, but also the systemic violence. Consequently, sharing a piece of the culture—everything that has been left—demands sharing a bigger picture of reality, communicating what happens to our community around the country, and demystifying a little of the stereotypical image that has been built without the agency of the ciganos themselves.

By Aila Regina da Silva

Notes

(1) Cigano(a) is the Brazilian word to refer to nomadic people called gypsy, recently reviewed as Roma, following the language Romani, originally from Rom. I chose to use the Brazilian word cigano(a) for two reasons. First, because I believe it’s important to fight for the word that unites us as a plural group, ciganos belong to different families, and I hear several ciganos and ciganas referring to themselves with pride instead of prejudice and racism. Second, there isn’t a consent among the Cigano community that all of us descend from Rom; in Brazil, it’s believed that there are three main branches: Rom, Sinti, and Kalons. Finally, it’s important to hear the majority from the inside; the considerations about Roma people came from academics and non-ciganos in my experience.

(2) Romani/Kalé word to refer to a non-cigano.

Works Cited

Albertine Dance Season. “Reciprocities: Making and Supporting Dance between France and the US.” Lecture “Acts of Transmission”. 26-27 Oct. 2023. <https://villa-albertine.org/events/albertine-dance-season-professional-symposium/>

Augusto Boal, et al. Theatre of the Oppressed. 1979. London, Pluto Press, 2019.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde e AMSK. Subsídios para o cuidado à saúde do povo cigano. Brasília, Ministério da Saúde, 2016.

Campt, Tina. Listening to Images. Durham ; London, Duke University Press, 2017.

Caruth, Cathy. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

China, José B. de Oliveira. Os ciganos do Brasil. São Paulo, Imprensa Oficial do Estado, 1936.

Connerton, Paul. How societies remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish : the Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books.

Greenberg, Zoe. “What Happens to #MeToo When a Feminist Is the Accused?” NY Times, Aug.13, 2018. Accessed Dec. 9, 2023. <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/13/nyregion/sexual-harassment-nyu-female-professor.html>

Goldfarb, Maria Patrícia Lopes et al. (org). Ciganos: olhares e perspectivas. João Pessoa, Editora UFPB, 2019.

Herman, Judith Lewis. Truth and Repair: How Trauma Survivors Envision Justice. New York, Basic Books, 2023.

Hessler, Stefanie. Frida Orupabo. MIT Press, 2 Aug. 2022.

Kilomba, Grada. Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism. Münster, Unrast, 2008.

Rauter, Cristina Mair Barros. “Os que vieram para branquear o Brasil: o moinho de gastar gente e a imigração alemã no século XIX.” Revista da Associação Brasileira de Pesquisadores/as Negros/As (ABPN), vol. 10, no. 24, Feb. 2018, pp. 67-88, <https://abpnrevista.org.br/site/article/view/574>

O’Neill, Linda et al. “Hidden Burdens: A Review of Intergenerational, Historical and Complex Trauma, Implications for Indigenous Families.” Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, vol. 11, 2018, pp. 173–186. <https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40653-016-0117-9>

Opie, David. “Why Killing Eve was canceled – and the chances of season 5 or a movie.” Digital Spy, April 8, 2022. Accessed Dec. 9, 2023. <www.digitalspy.com/tv/a39649462/killing-eve-cancelled-season-5-movie/>

Senado Federal. “Estatuto dos povos ciganos é aprovado e vai à Câmara.” Agência Senado, 3 May 2022. <https://www12.senado.leg.br/noticias/materias/2022/05/02/estatuto-dos-povos-ciganos-e-aprovado-e-deve-seguir-para-a-camara>

Silva Júnior, Aluísio de Azevedo. Produção social dos sentidos em processos interculturais de comunicação e saúde: a apropriação das políticas públicas de saúde para ciganos no Brasil e em Portugal. Rio de Janeiro, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, 2018. PhD dissertation.

Skidmore, Thomas E. Fact and Myth: Discovering a Racial Problem in Brazil. Kellogg Institute: Working Paper 173, April 1992. <https://kellogg.nd.edu/sites/default/files/old_files/documents/173_0.pdf>

Silva, Denise Ferreira. 2017. “Unpayable Debt: Reading Scenes of Value against the Arrow of Time” The documenta 14 Reader. Edited by Quinn Latimer, and Adam Szymczyk. 81-113. Kassel, Munich: documenta and Museum Fridericianum, Prestel Verlag,

Silva, Denise Ferreira. Toward a Global Idea of Race. University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Taylor, Diana. ¡Presente!: The Politics of Presence. Durham, Duke University Press, 2020.

Taylor, Diana. “You Are Here”: H.I.J.O.S. and the DNA of Performance” The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. 161-189. Durham: DukeUniversity Press, 2003.

Van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma. London, Penguin Books, 2014.

Yao, Xine. “Xine Yao, Disaffected: The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America.” www.youtube.com, www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSh-V2sPLU4. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

Yao, Xine. Disaffected : The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America. Durham, Duke University Press, 2021.

David, Opie. "Why Killing Eve was canceled – and the chances of season 5 or a movie.." Digital Spy, 9 Dec 2023. Accessed www.digitalspy.com/tv/a39649462/killing-eve-cancelled-season-5-movie/. Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish : the Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books, Connerton, Paul. How societies remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. Kolk, Bassel van der. 2014. "Part IV: The Imprint of Trauma" The Body Keeps the Score. 204-237. New York, New York: Penguin Random House, Yao, Xine. Disaffected: The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America. Durham: Duke Univeristy Press, 2021. Print.Hessler, Stefanie. Frida Orupabo. MIT Press: MIT Press, 2022. Print.Yao, Xine. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSh-V2sPLU4 Brown University, Web. 4 Dec 2023. Caruth, Cathy. 1995. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, Herman, Judith Lewis. 2023. Truth and repair: how trauma survivors envision justice. New York, NY: Basic Books, Hachette Book Group, Taylor, Diana. 2003. ""You Are Here": H.I.J.O.S. and the DNA of Performance" The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. 161-189. Durham: Duke University Press, da Silva, Denise Ferreira. 2017. "Unpayable Debt: Reading Scenes of Value against the Arrow of Time" The documenta 14 Reader. Edited by Quinn Latimer, and Adam Szymczyk. 81-113. Kassel, Munich: documenta and Museum Fridericianum, Prestel Verlag,