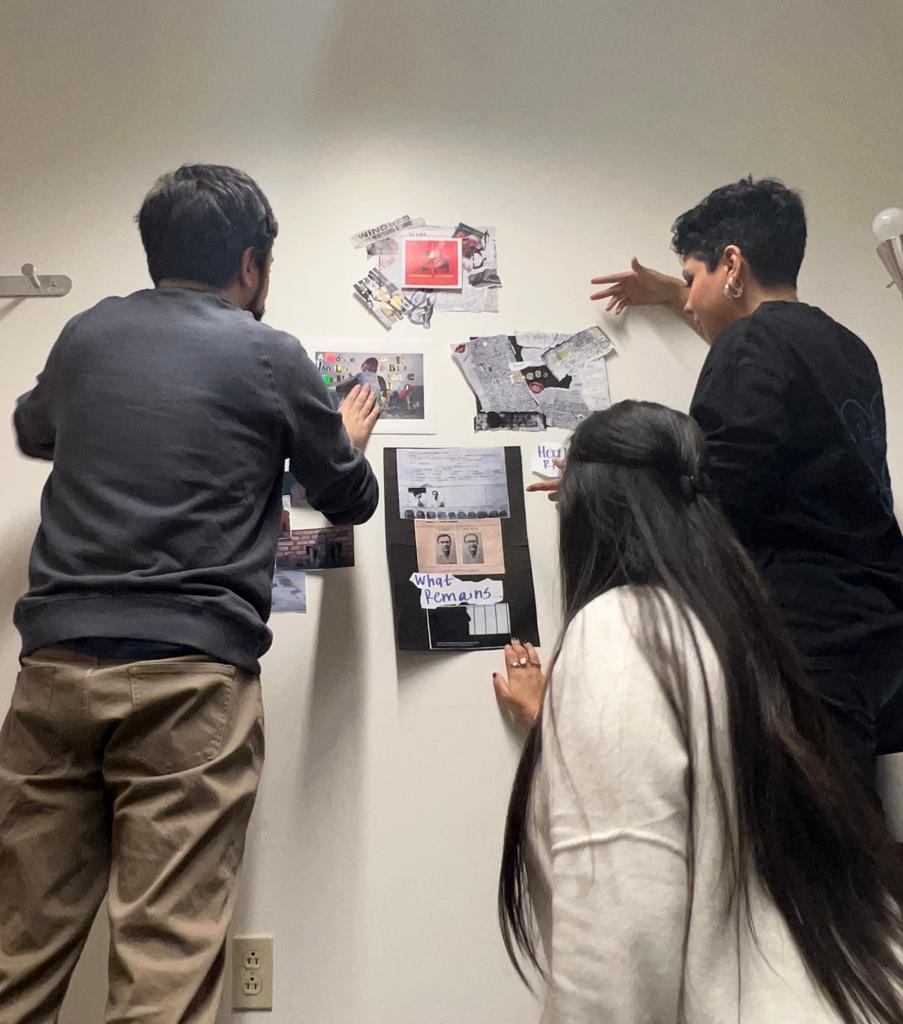

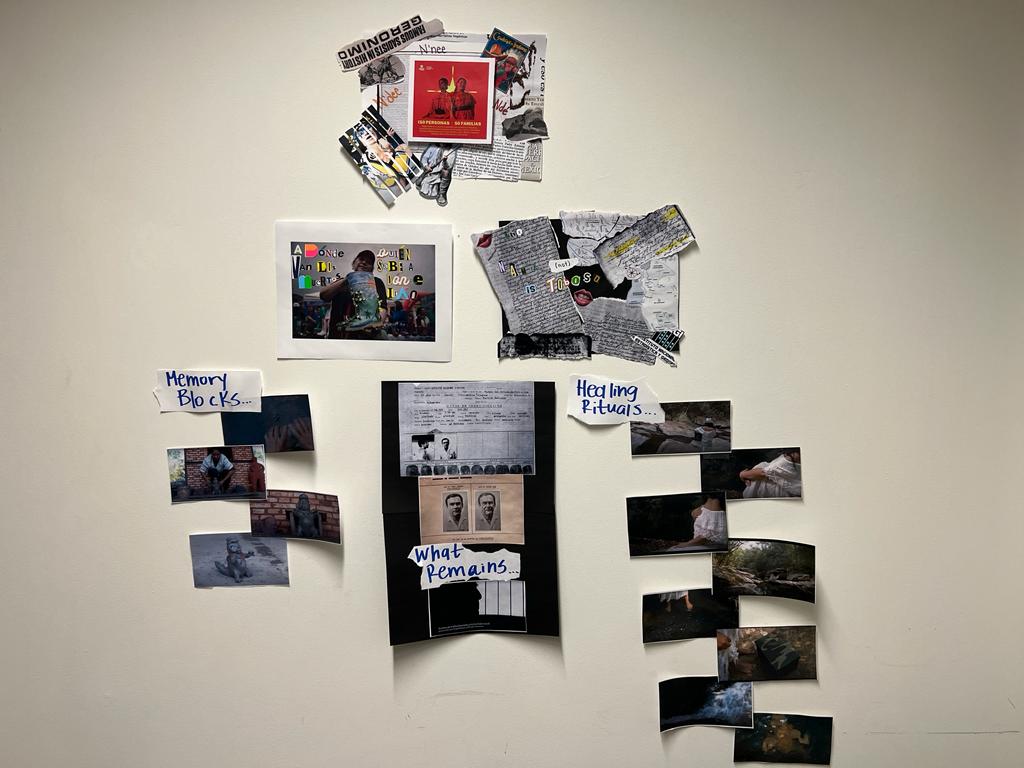

Figure 1. Our intervetions.

Figure 1. Our intervetions.

Our project centers around dis-appearances of marginalized communities. This chapter focuses on six instances of dis-appearances: forced disappearance, false incrimination, misnaming, acculturation, invisibilization, and political imprisonment. We are developing these instances with case studies from our countries: Colombia, México, and Paraguay. We rely on the concepts of trauma, memory, and performance of Sigmund Freud, Cathy Caruth, Judith Herman, Bessel van der Kolk, and Diana Taylor to expand the idea of disappearances and their consequences in two ways. On the one hand, we want to emphasize that disappearing entails a much broader process than only killing people. It is always part of a systemic, political, and economic project that impacts the affected peoples and their broader communities effectively and psychologically. Consequently, disappearances disturb their day-to-day individual and social practices. On the other hand, we argue that what is attempted to disappear always leaves a trace. Disappearances are never absolute. Nothing disappears completely.

The void left by what “disappears” is not entirely empty. For our title, and in specific instances, we write disappearance vis-á-vis dis-appearance with a hyphen to denote our main argument: that which remains always resurfaces. Even in the cases when the state’s official narrative presents that something or someone has disappeared as Truth, we can still find traces of the disappeared in the archives, literature, diverse media, objects, people, and places. These sites of memory –we understand sites as not only physical places– can be co-opted by the same systems that produced the disappearance. The sites can also be reactivated by marginalized communities in order to recuperate memory and contest violence.

In this way, we will relate why and how we use trauma, memory, and performance in this Introduction to frame the chapter. For Caruth, in the “Introduction” of Recapturing the Past, trauma “registers the force of an experience that is not yet fully owned” (1995, 151). That means, for her, that trauma “has no [temporal] place” in a person’s mind; it is an event that, “in its unexpectedness or horror,” cannot be “fully integrated as it occurred” and “thus continually returns” (1995, 153). This goes hand in hand with van der Kolk’s definition. For him, trauma is what “is unbearable and intolerable” (2014, 14): it is a horror that overwhelms and breaks down the system of a person (2014, 211). Defining trauma, then, is not so much about the event but the impressions that remain on the person who lives it. Who knows what can cause trauma: trauma is always the experience after the event. The disappearance of someone is a deeply traumatic event for the people left behind. Thus, we can use the studies on trauma to argue that every disappearance leaves traces on the individual and collective bodies. Maybe, for this reason, it is so important for Herman to highlight that trauma, even if it was lived individually, is always communal: “If trauma shames and isolates, the recovery must take place in community (…) [it] cannot be simply a private, individual matter” (2023, 8-9). Every disappearance is experienced, as a trauma, over and over again.

We argue that what is attempted to disappear always leaves a trace. Disappearances are never absolute. Nothing disappears completely.

The following question could be: what do we do with this particular trauma? According to Freud, the aim of his work as a psychoanalyst “is to fill in gaps in memory; dynamically speaking, it is to overcome resistances due to repression” (1924, 148). In the same way, communities and families around the disappeared need to find other ways to fight back against those gaps born out of a repressive state. The affected “continue the practice of keeping the disappeared ‘alive’” (Taylor 1997, 140) by unearthing their remains using the aforementioned sites of memory.

Furthermore, for Freud, the “repressed” (he never speaks about trauma) is “acted out” instead of being remembered (1924, 150). For this reason, the concept of performance is also essential to us. We can understand that what the disappeared leave behind is also “acted out” in communities and families, in objects and places, consciously or unconsciously. This is not necessarily the performance of the disappeared but of their traces, memories, and pain. To keep the disappeared “alive” in the present historical moment, people create symbolic and material manifestations such as monuments, artistic pieces, or social movements. For example, in Ciudad Juárez, México, a city famous for its femicides and disappearances of women, the local feminist activists fill the city with pink crosses so people are not oblivious to what occurred and continues happening. The state usually erases these crosses, but the families and activists always find new ways to repaint them.

We do not limit the concept of performance to artistic or activist practices. Everything that acts performs. A word, a room, an object, or a specific place can “act out” a traumatic event. To make such a claim, we expand Freud’s notion of “acting out” to the relationship between the human and the non-human. As he understands that traumatized people “act out” the trauma through their behavior, we argue that sites can also “act out” what has been repressed in them. For our project, what these sites “act out” are the remains of the disappeared: their memories and fragmented presences. We are thinking, for example, about the moment when Taylor visits Villa Grimaldi, the former torture center of Chile’s dictatorship, with a victim. When Taylor asks the victim, Teresa Anativia, if returning to the site upsets her, she replies that she does not recognize the place: “But [her] bones hurt” (2020, 197). The place activates something in her body, which remembers what her mind does not.

Therefore, we argue that disappearance is another instrument to control populations and impose a national identity and history, and ethnic hegemony. In the Latin American cases we study, we identify an imposition of a white Eurocentric standard of being and existing. For a state to erase and exclude populations or individuals from the archives, to deny their existence, denigrate or invisibilize them, and also, of course, to kill and kidnap is a political project. Nations are built through the notion of citizenship: those who are not regarded as full citizens, i.e., those who do not comply with the national identity and racial hegemony the state wants to impose, are the ones most vulnerable to be disappeared. Hence, to state that something always remains after a disappearance is a political stance in the sense that what remains resists these colonial and imperial projects. This chapter highlights that although states feel they are in control of the population, they are not. At least, not completely.

We do not limit the concept of performance to artistic or activist practices. Everything that acts performs. A word, a room, an object, or a specific place can “act out” a traumatic event.

In our personal scholarly work, we are invested in researching these specific communities in our countries: Colombia, México, and Paraguay. Thus, each of us reviews two specific instances of dis-appearances in different writing styles that connect with our research interests. Juan Diego Arias explores forced disappearance and false incrimination in Colombia; Grecia Márquez García analyzes misnaming and acculturation in México, and Delicia Alarcón engages with invisibilization and political imprisonment in Paraguay. Each writing is based on different archives and cultural artifacts: photos, flyers, colonial letters, census reports, police and judicial records, art pieces, and videos. As we mentioned, objects perform. Thus, in this project, we also intervene and reactivate this archival media in a performative way. We take stills, create collages, and curate the images consciously throughout the chapter in such a way that they not only illustrate the writing but animate it.

Finally, we outline what the reader will find in the following sections. In the first one, Juan Arias explores forced disappearance through a judicial record used to incriminate a Colombian Army general who participated in the disappearance of civilians during the siege of the Palacio de Justicia after the M-19 urban guerrillas took it over on November 6th and 7th, 1985. He then thinks about false incrimination from a plastic boot intervened by the mother of one of the victims of the falsos positivos. Falsos positivos is a practice used by the Colombian army by which the soldiers kill civilians and disguise them as guerrillas in order to receive promotions or other benefits. Between 2002 and 2008, this practice left more than six thousand victims, who were poor and mentally disabled young men.

Guided by official documents, Grecia Márquez proposes that the (mis)naming practices exerted by the governments of the North of New Spain, and now the North of México, contributed an essential part to the declaring and disputing of the “Toboso” peoples’ extinction. In her following contribution, she acknowledges how acculturation and the myth of mestizaje also played a crucial role in the manipulation and erasure of the history of existence and resistance of the N’nee/N’dee/Ndé nation in the same region. A Facebook flyer posted by the native nations’ representatives, she contends, defies this acculturation.

Delicia Alarcón uses stills from the documentary Calle de silencio about the niñas esclavas (girl slaves) during the Stroessner Regime in Paraguay as a cultural artifact and testimony of invisibilization. Alarcón argues that the organized disappearances and invisibilization of these young girls remain in the sites where these sexual violences occurred. Later, she explores political imprisonment through the police record of Rogelio Goíburu. This record from the Archivo de Terror (Archive of Terror) in Asunción indicates that even though he was captured and violently disappeared by the military regime, his physical remains and other disappeared bodies still exist in mass graves somewhere in Paraguay.

Juan Diego Arias explores forced disappearance and false incrimination in Colombia; Grecia Márquez García analyzes misnaming and acculturation in México, and Delicia Alarcón engages with invisibilization and political imprisonment in Paraguay.

As we said in the beginning, in this chapter, we flesh out the notion of disappearance as well as demonstrate that it is not always absolute. Most importantly, we hope to contribute to reparative memory in order for these traumatic events not to be forgotten.

Between the blurred and the obvious: The forced disappearances in the Palacio de Justicia (1985, Colombia):

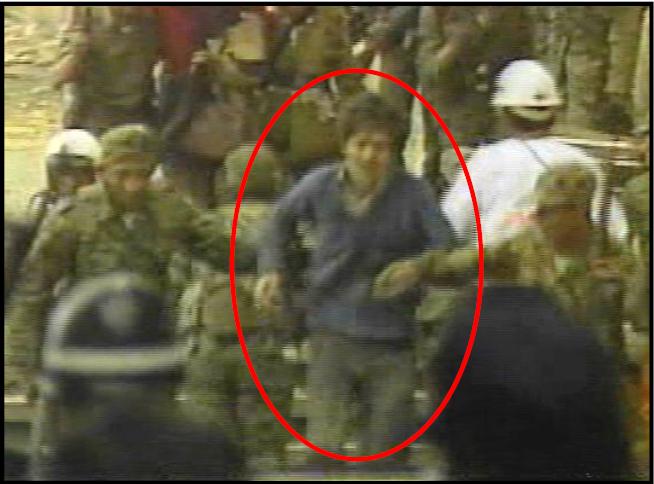

The image was taken from a video broadcast by the Televisión Española (TVE) on November 7, 1985 (Figure 2). The bodies are in motion. Likewise, the image has been cropped and enlarged; it is pixelated. As in the photographs where ghosts are sighted, a red oval highlights a figure. However, the figure is not hidden: it is the one that dominates the photo; it is its center, its core: a man wearing what appears to be a blue sweater, a light shirt, and a pair of jeans. The facial features are harder to recognize. His skin is white. His hair is black. His hair is short on the sides but grows upwards. He looks shocked and weak. He does not seem to walk easily. Perhaps he cries. Maybe he’s wailing. He does not look straight ahead. Nor is it clear that he is looking at the floor. Perhaps his gaze is lost amidst the tears(?). Two other men in military uniforms help him, guide him. They carry him. Behind him is a man in white from the Red Cross. Around him, other figures are more difficult to recognize: it is possible to distinguish several military men and a couple of civilians.

Figure 2: Still from a TVE broadcast. The still was used as a juridical record of forced disappearance by the Tribunal Superior del Distrito Judicial de Bogotá (Superior Court of the Judicial District of Bogotá) against a General of the Colombian Army.

Figure 2: Still from a TVE broadcast. The still was used as a juridical record of forced disappearance by the Tribunal Superior del Distrito Judicial de Bogotá (Superior Court of the Judicial District of Bogotá) against a General of the Colombian Army.

And although he is visibly a person of flesh and blood, what is traced in red is a ghost. The image is taken from TVE’s broadcast of the takeover of the Palacio de Justicia by the M-19 urban guerrilla on November 6th and 7th, 1985, in Bogotá, Colombia. The ghost is Carlos Augusto Rodríguez Vera, manager of the Palacio’s cafeteria. Those accompanying him were members of the Colombian Army, who, by order of the president at the time, Belisario Betancur, forced their way into the Palacio without any attempt at conciliation. That forced entry left 94 dead and 12 people missing (Cnmh 2020).

Carlos is one of them. The military men who accompany him do not help him, but they do guide him. They are probably taking him to the Casa del Florero, a historical museum in downtown Bogotá, very close to the Palacio. There, Carlos will be tortured and then disappeared. Despite being a cafeteria manager, the military wants information about the guerrilla attack at any cost. This is just one more case of forced disappearance in the country: people detained by a State that then denies or refuses to say where they are. In 2013, the State accepted its responsibility for this and 11 other cases of forced disappearance after the military intervention in the Palacio de Justicia (Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos).

However, Carlos is still a ghost. No one knows where his body is. While the national media was showing a soccer match and trying to distract the audience from what was happening in downtown Bogotá, Carlos’ father saw him leaving the Palacio alive in the TVE broadcast (El Espectador 2017). This image, which highlights the ghost, was used as evidence against the military commanders who led the retaking of the palace (Tribunal Superior del Distrito Judicial de Bogotá 2013).

To say that Carlos lives in this photo would be unfair to the family, especially his daughter, who was 35 days old when her father disappeared (Idrobo). To say that the photo represents those who disappeared from the Palacio de Justicia is helpful, as the image is proof of state brutality, but it is still an understatement. There are photographs of the siege at the Palacio that are more aesthetic and more telling, more violent and clearer. However, between the blurred and the distorted, between the undefinable and the illegible, there is the presence of Carlos. That his face cannot be seen clearly shows the cruelty of forced disappearance. That the soldiers at his side seem to help him, almost to save him, illustrates how the violence of the Colombian State operates. Without a grave to mourn him, without a body to bury or cremate, Carlos is that ghost they wanted to erase. However, different hands have had to trace that red oval to show that he is there, that he can be seen: that he did not disappear, the State disappeared him.

Juan Arias

How the Disappeared Became Boots: The Case of the Falsos Positivos (2002-2008, Colombia):

The disappeared circulate. As their presence is incorporeal, nothing holds them to the ground. For the families looking for them, one day they are at work or at school, and the next they are at a friend’s house, a park, a bar, lost, in an accident, maybe they ran away… Their incorporeality makes them invisible to the eyes but also makes them present everywhere: they are in memories, in photos, in their rooms, in the streets where they used to walk. As Michelle Castañeda says, “A person is in either one place or another. A person can be here or there but not both. Except if they are disappeared” (2023, 131).

However, they are also incorporeal to those who disappear them. In the more than 60 years of civil war in Colombia, it was not unusual for members of the National Army to lure civilians, especially the poor and mentally disabled, with offers of work, kill them, and change their clothes to disguise them as guerrillas (Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular 2011). They would take photos of the dead bodies. For the families, these people never reappeared. Between 2002 and 2008, this practice became normalized (Izagirre 2014). More than six thousand people, mostly young men, mostly living in the countryside or in the suburbs of the cities, were disappeared by the State in this way. There, too, they began to circulate.

For the government, which demanded guerrilla casualties and gave rewards to soldiers who showed proof of this, they began to become numbers. For the journalists who began to discover inconsistencies in the photos, they began to become objects. They would discover that the position of the weapons did not match that of a combatant or that the boots were incorrectly placed: boots on the wrong foot or with two right or left boots on the two feet. No one could walk through the jungle with boots like that (Revista Semana 2020). The disappeared became boots. Plastic boots. Pantaneras, as they are called in Colombia. Those boots are the ones that distinguish a guerrilla from a military man: in the Army, they wear leather boots.

With the embarrassment of the situation (the Colombian Army was killing civilians by disguising them as guerrillas), they began to circulate under another name. Falsos positivos, they began to call them, a term used militarily that comes from a medical concept that refers to pregnancies or illnesses that the patient feels but, in reality, does not have (Rae). Uncorporeal, they were now a non-existent disease, hypochondriac cases.

The families searching for them recognized their sons, brothers, and cousins in photos, wearing uniforms they had never worn in their lives. However, not all the bodies reappeared. That is why they continued to circulate. And members of the State, with no arguments to defend the cases, disguised them again: they judged them, blamed them for their own disappearance and death; surely, they claimed, if they were dead, it was because they had done something (Izagirre 2014). The State disappeared them in order to change their identity; it transfigured them. It took advantage of the incorporeality of the disappeared to mold them to their liking.

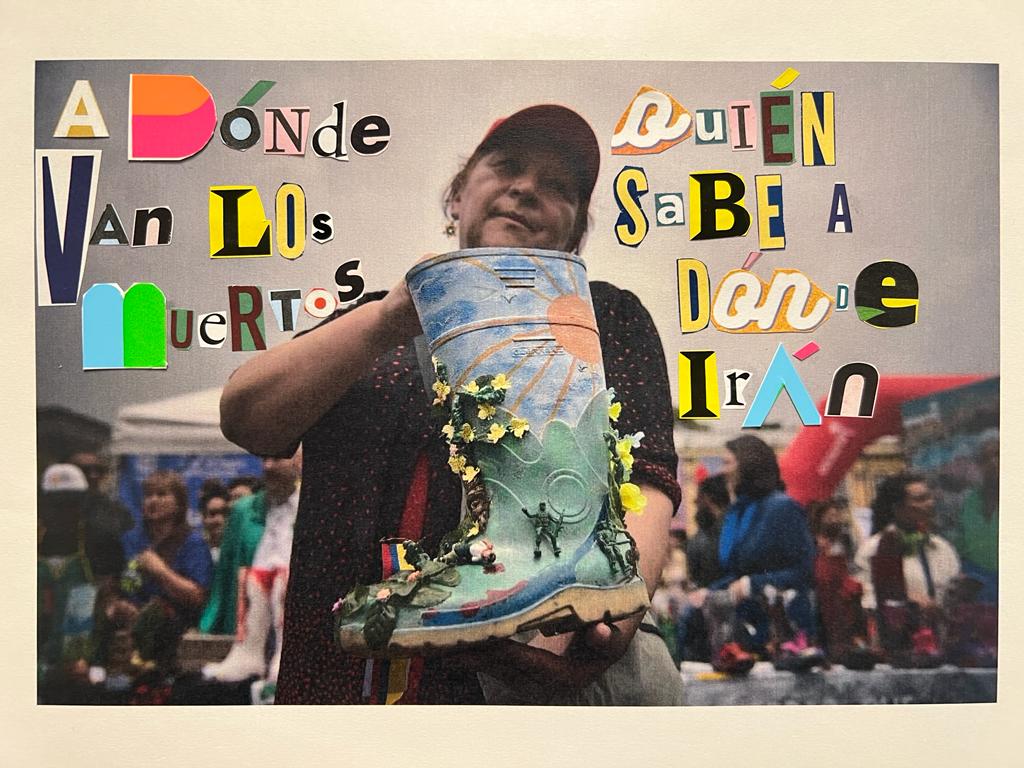

They continue to circulate. With the ability to also define where they circulate, the Asociación de Madres de Falsos Positivos (MAFAPO) is claiming their presence in plastic boots that they are intervening. The disappeared were already boots. Now they are the boots that the mothers are choosing: they are painting them, writing on them, adding details about them or about their disappearance. They are sculptures, manifestations of an act of violence; they are a protest. They are also a remembrance. Cecilia, who appears in Figure 3 and who decided to recreate the scene in which her son was killed in the boot, says: “Cuando uno pinta, pasa lo mismo que cuando uno cose: se piensan y se mastican las cosas que uno tiene atoradas en el alma” (“When you paint, the same thing happens as when you sew: you think and chew on the things you have stuck in your soul”) (Cnmh 2023).

The disappeared do not stop circulating. They are thought and rethought by those who lost them. They remain stuck in the souls of their families, but not as falsos positivos: they are a real disease. Now, these missing persons circulate in artistic pieces, which have their own ways of circulating. Incorporeal, still, they are figurative and disfigured. They are not here, but they have the potential to be everywhere.

Juan Arias

Figure 3. “«Mujeres con las botas bien puestas»: las madres de Soacha quieren contarle al mundo su lucha contra la impunidad.” Photograph taken by Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica with Juan Arias’s intervention. The image reads: “A dónde irán los muertos, quién sabe a dónde irán” (“Where do the dead go, who knows where they go”).

Figure 3. “«Mujeres con las botas bien puestas»: las madres de Soacha quieren contarle al mundo su lucha contra la impunidad.” Photograph taken by Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica with Juan Arias’s intervention. The image reads: “A dónde irán los muertos, quién sabe a dónde irán” (“Where do the dead go, who knows where they go”).

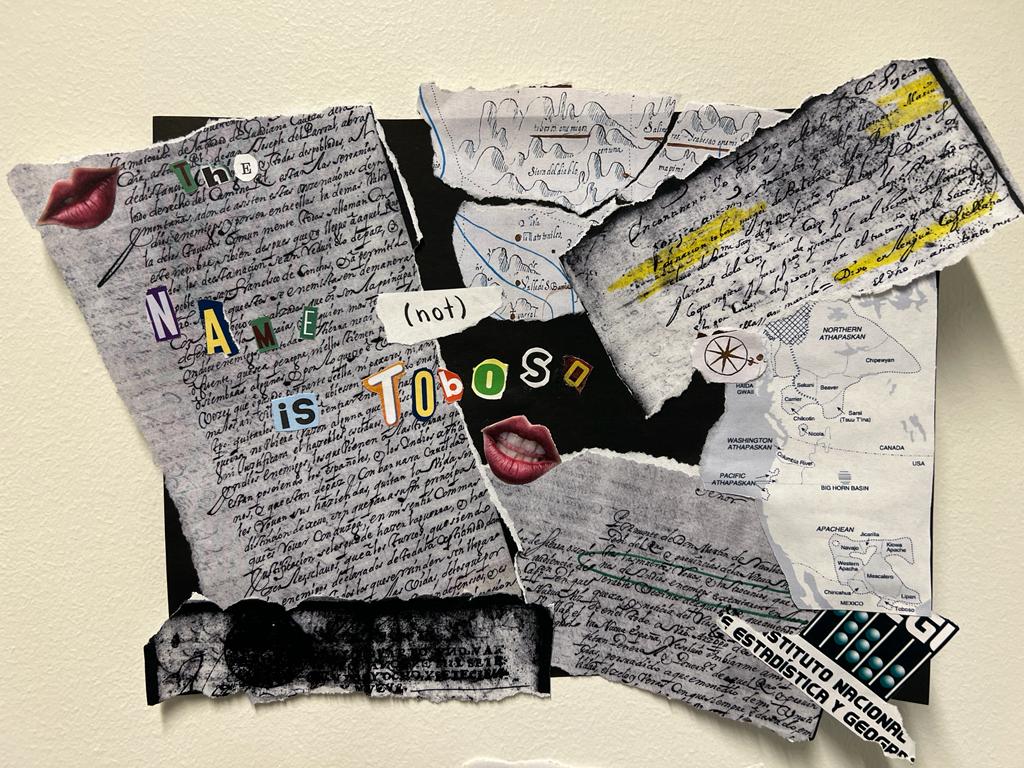

Not your name: On the politics of (mis)naming the “Toboso” peoples during the colonial period and the current times

A letter dated September 29th, 1678, sent by the former governor of New Vizcaya (one of the Northern kingdoms of New Spain, now parts of the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Coahuila), Lope de Sierra Osorio, constitutes an example of a very common practice during the colonies, one whose legacy has expanded until today: the settlers would call the local natives by words other than their own names. This titles, commonly known as “exonyms” (Giraut, 84), denominations imposed by people exterior to the groups that they identified, were especially enforced by the colonizers over some native groups in the Americas seen as of second importance in relation to others. In some cases, the exonyms would be words in other “more important” native languages seen as lingua francas, such as the Nahuatl. In the case of one of the groups Sierra referred to, a European name was used, “Toboso”.

The choosing of this expression is unclear, however, we could infer two possible origins: that it was the lastname or place of birth of their Iberic “discoverer” or another figure of main importance in their first period of contact with the foreigners. The second option is that this name was chosen due to its semantic charge. According to the 1611 dictionary by Sebastián de Covarrubias Orozco (Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española), “tova” means a rock commonly found on caverns. These people were described as living in caverns, a convenient image for the European who saw this type of proximity to nature as primitive and barbaric.

The same letter reveals something even more astonishing: if, in the beginning, “Toboso” designated only one group, later on the colonizers decided to call a number of different native communities by the same name, homogenizing all differences between them: “adonde asisten estas onze naciones de yndios enemigos y por ser entre ellas la de mas valor la de los tovossos comunmente todas se llaman con este nombre” (“where these eleven nations of hostile Indians live. Because the bravest among them are the Tobosos, all are commonly called by this name”).

But why do names matter so much, specially in relation to disappearance. First of all, the act of naming and fixing those names in the archive, in the colonial logic demonstrates an exercise of power, an expression of dominance, that of being able to substract the agency of the others over themselves, coopting their identity, at least simbolically. Postcolonial scholar Julietta Singh, while analyzing the 1999 book by Jamaica Kincaid My Garden, pointed out that “there is a crucial continuity among the colonial, the botanical, and the ecotouristic in that they perform the possessive erasures of others, enforcing masterful world relations by naming others as if they exist for oneself” (Singh, 166). The original terms as well as their semantic and metaphoric load get erased. This erasure can lead to their eventual loss. And what happens to a community that no longer exists in their own terms? How to carry on living with this trauma?

Going back to the document, although in the beginning they are called the “bravest” (also meaning the most “hostile”), if we continue reading the letter, it soon declares that the “Toboso” eventually became part of the principle defenses of the kingdom: “despues que yo llegue a aquel Reino todos los de esta nazion se han reducido de paz […] a permitido Nuestro Señor que estos se enemistasen de manera con las naziones alzados que hoi son la principal defensa de la Vizcaia, y a quien mas temen los yndios enemigos” (“after I arrived in that kingdom all those of this nation were reduced to peace […] Our Lord has permitted that they should become such enemies to the rebellious nations that today they are the principal defense of [Nueva] Vizcaya, and are those whom the hostile Indians fear most”).

There seems to be a conflict between the juxtaposition of the two characterizations of the “Tobosos” as “fierce” and “domesticated”. Nonetheless, Sierra could condense in these two adjectives the conflicted history of the relation of the European with this group until then: during the first scouting of the region, marking the “Tobosos” with adjectives that denoted ferocity would justify their persecution and genocide; after the establishing of Spanish settlements, calling them “docile” and “allies” would allow their integration in the colonies and using them for labor in the mines, fields and houses. So what in the beginning constituted a also a naming practice that enabled their physical extermination, eventually changed to a more subtle, although still violent, strategy that would favor the sustenance of colonial societies.

Even if colonialism always ensues high levels of trauma for the colonized (that of the exploitation of their bodies, their lands, and the erasing of their history, values and worlds), we can still find expressions of resistance and self-affirmation in the archives and in other repertoires. Another instance of erasure, perhaps even more directly related to the intention of disappearing the “Tobosos” as such, was that, due to their apparent population reduction caused by disbandment, displacement and the confusion with who were the original actual “Tobosos” and who were the adjunct, by the ending of the administration of Sierra, by the last decades of the seventeenth century the “Tobosos” were thought to be virtually extinct. Nevertheless, there’s documents from later decades where individuals claim to belong to the “Toboso nation”; paradoxically, nowadays latest Mexican censuses don’t register the “Tobosos”, but the 2015 instructions for filling the surveys do enlist the “Toboso” in the native languages section; and what’s more, even if this referred to other possible indigenous “Tobosos” in México, in my personal history there’s a “Tobosa” ancestor on my father’s side, four generations away from mine, born possibly at the end of the nineteenth century in the same region the “first” “Tobosos” inhabited. All of these hints to the fragmented lives of the “Tobosos” can be put together to hold a thesis, that these people are somehow still here.

Figure 4. Grecia Márquez’ intervention.

Figure 4. Grecia Márquez’ intervention.

Between the dichotomy of the violence exerted by and through the exonyms and the constant struggle of looking for the recuperation of the endonyms as a means to bring back important parts of the stories stripped, choosing to pay attention to the history of peoples considered “minor” and currently “disappeared”, even if it means utilizing the colonizers words, conveys contesting the myth that these peoples ever disappeared, that their memory was ever totally destroyed. To give a partial answer to the question of what happens to a community that no longer exists in their own terms, I suggest that even without the proper names, among other things, by reappropriating the forced upon ones and choosing to identify with them –at least in face of the colonial system–, the community can continue to perpetuate itself through time. The question becomes a tricky one. I think that looking for those endonyms is still necessary, but I don’t think there’s any reason for protesting the reappropriation. To demand originality would also be a recolonial gesture in that it would imply that the only legitimate “Tobosos” were the ones that never called themselves like that. In these scenarios, to name others and to claim such names for oneself is political. The famously quoted Shakespearean phrase from Romeo and Juliet, “What’s in a name?” continues as follows: “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell just as sweet”. Read with the fact that naming can be done in favor of effacing the “true identity” in mind, one could say that, as romantic, colonial too, as the British citation might appear, there’s some truth in it: regardless of how it’s called, that that was objectified and taxonomized, has the power to survive… but that would depend on the rose and not on the botanist.

Grecia Márquez

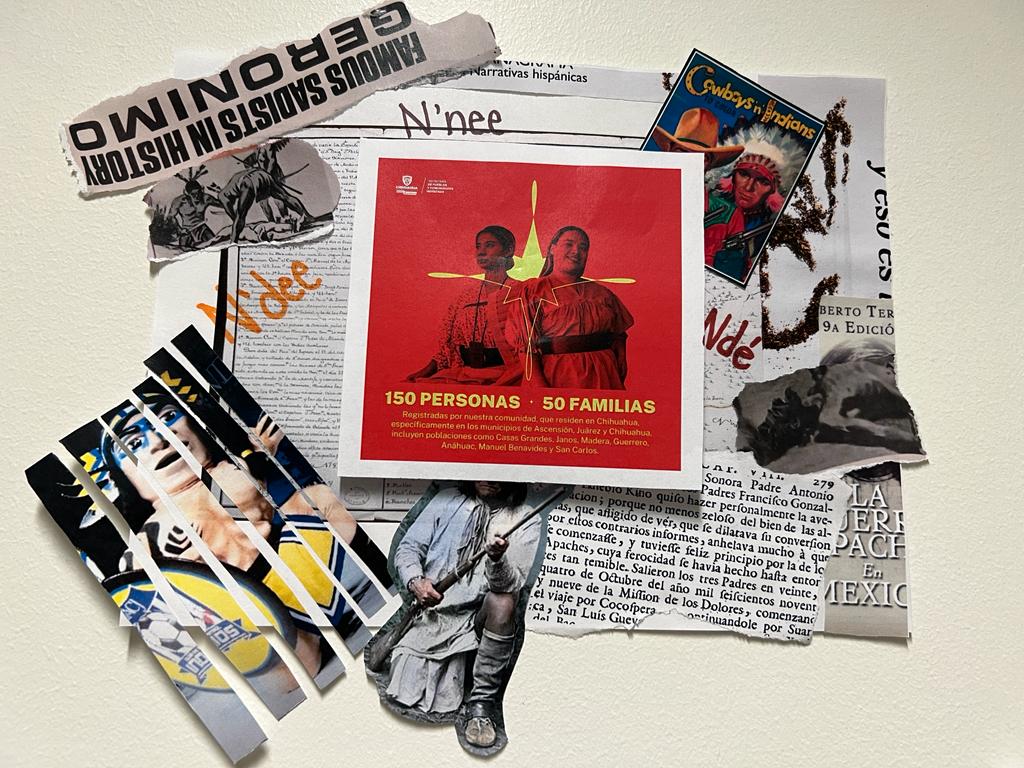

Despite mainstream culture: the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé project against acculturation

Figure 5. Grecia Márquez’ second intervention.

Figure 5. Grecia Márquez’ second intervention.

The N’dee/N’nee/Ndé nation’s history in México is often ignored by the vast majority of the population. We often picture them only as part of the United State’s former times; their hunting and killing is glorified over and over again by dozens of Western movies, comics and literature. Most of those who do know about the presence of the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé don’t even know them by these names, they just call them “Apaches”, partly influenced by the American, partly by other Mexican historians, writers and institutions. Here, we need to go back to the previous piece about the significance of names, and the particular uses some groups give to their exonyms. The word “Apache” comes from the A:shiwi and means “enemy” (Longoria, 19). Much like the “Tobosos”, the “American” “Apaches” are choosing to strategically appropriate this vocative. However, according to the sociolinguist Denisse Gómez Retana, for the communities distributed throughout the Mexican territory (in the states of Chihuahua, Sonora, Coahuila, and Durango) it is crucial to name them under these three variants of their endonym, given that they “represent all of the tribes discursively as well as in the decision making” (Gómez 2023).

Unlike the U.S., that decided to create indigenous reservations, the Mexican society sought to distort and erase all forms of memory that ascertain that the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé are still alive and justly fighting for recognition. It wasn’t until December of 2022, and October of 2023 that the states of Coahuila and Sonora formally acknowledged them as native groups within these territories, “granting them” the right to “preserve and develop their language, customs, uses, traditions, religions and everything else that distinguishes them” (Gobierno de Sonora, 7). Until this moment, at a federal level, their inclusion in the National Catalog of Pueblos and Indigenous Communities authorized by the National Institute of Indigenous Pueblos is under revision (INPI, 2), before that, they were marked as “extinct”. In the case of Chihuahua, while some of its internal organisms (and political parties) work along some of the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé representatives for educating on their culture and recognition of their rights, the state officially has yet to concede them as an originary nation (ZonaFree, 2023).

The relationship between the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé and this last state is full of practices and figures that complicate said recognition. Cultural products and artifacts similar to those circulating in the Northern neighboring country proliferate on the Mexican territory as well. Even if not all of them misrepresent the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé, a lot of them do. For instance, in 2012, the Chihuahuan historian and lawyer, my high school professor, Filiberto Terrazas Sánchez made me and my classmates read his 1974 novel where, maybe not surprisingly, he calls the nineteenth century Terrazas family a “fine stirpe” (Terrazas, 14). From that family, Joaquín Terrazas, was directly responsible for the persecution and genocide of the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé during the last decades of said century. We were being taught the story of the “civilized” peoples’ victory over the “barbarians”, that this massacre was not only necessary but good and that we should be proud of it as Mexican Chihuahuans. On the other hand, that institutions like universities use indigenous peoples as mascots is not new. The football club of the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez (UACJ) is called “Indios” (Indians), and they use Goyaałé, better known as Gerónimo, a nineteenth-century leader, as their mascot. This is even more upsetting if we consider that Goyaałé was exhibited in American fairs and state events for the last decade of his life. By tokenizing key figures like Goyaałé, instead of paying homage, the educational institution contributes to spreading the notion that the “Apaches” are a thing of the past, peoples we can caricaturize and use for the public’s entertainment. These representations of the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé constitute performances of cultural appropriation that are rooted in racism.

In a broad sense, acculturation is “any change that results from contact between individuals, or groups of individuals, and those from different cultural backgrounds” (Merton, vii). One of those possible outcomes is the assimilation of the main culture and “rejecting the own” (Smith Castro, 30). With this in mind, we can better understand how the narrative of mestizaje became so widespread in Mexico as a tool for survival. In the examples from the previous paragraph about racism, and in many other instances the reader could think of, the indigenous are presented as the oppressed due to their writing into history as the barbarians (even when supposedly exalted for their bravery, as in the election of the mascots). Ascribing to acculturation causes the majority of the population to reject their own relation to indigeneity, in an attempt to gain proximity to whiteness. The Mixe linguist Yásnaya E. Aguilar Gil, following the arguments proposed in 1987 by Guillermo Bonfill, claims that in México through mestizo culture we have been disindigenized (Aguilar, 2018).

While identifying with the mestizo or mestiza does not necessarily mean accepting entirely the state’s ideology, its weight has had a definite impact on the disbanding and seeming disappearance of native groups in México. Nevertheless, the N’dee/N’nee/Ndé are fighting acculturation –and the correlative idea of extinction–, in many ways. First, they are presenting themselves as an indigenous nation native to the country. Aguilar also argues that “México is a state, not a nation. México is a state that has encapsulated and negated the existence of many nations. The Mexican constitution is very eloquent regarding the establishment of those equivalences when it enunciates that ‘the Mexican nation is one and indivisible’. If it really was, it would not be necessary to decree it” (Ibid.). On the other hand, they are constituting a digital archive through their social media where they document and share information about their history and current actions. This way, they resist mainstream narratives. Finally, they have an ongoing project for looking out for and registering other N’dee/N’nee/Ndé families. This is even more significative if we consider that they have been found living in the territories where historical massacres happened, like Casas Grandes and Janos. With all these strategies, the native nation contests the very idea that even those genocides could extinguish them. They never left. They never disappeared. And also, they are not what Mexican mainstream culture has labeled them as from outside.

The image at the center of the collage presented here was taken from their social media (with the permission of its administrators), and as the reader can notice, it has official state logos. This is also a reminder of the complex relationship and dialogues with the different levels and representatives of government the native groups have to sustain. While the rejection of mestizaje, the term “Apache”, and the way their story has been told is clear, they still need to confront the inevitable, that their territories continue being administered by the state. In order to gain visibility and change their current living conditions, their struggle has to have many fronts, some positioning them in ambiguity, dialoguing directly with parts of the system that have pretended to erase them before.

Grecia Márquez

Invisibilization made Visible: The case of “niñas esclavas” (girl slaves) in Asunción, Paraguay

Through testimony and sharing one’s story vicitms of extreme trauma and sexual violence can heal. The documentary Calle de silencio (2017) about the “niñas esclavas” (girl slaves) during the Stroessner Regime (1935-1989) in Paraguay as a cultural artifact. Through testimony and performance in the film and specific stills from the documentary, I argue that their invisibilization is made visible. The girl slaves who were either kidnapped or sold by their parents to the military leaders were between the ages of 10-15. I name these atrocities as the invisibilization of these young girls because some of them would never return to their homes, some murdered and found dead in Barrio Sajonia in one of the houses where the events happened, and others nowhere to be found. There is no trace of these young girls in the Archivo de Terror (Archive of Terror), the main archive of documents produced by the regime. Over the course of the years the Comisión de verdad y justicia (CVJ, commission of truth and justice) was created in 2003 by the Ley de la Nación N° 2225/03 to investigate the human rights violations in Paraguay from 1954 to 2003. Therefore, the organized disappearances and invisibilization of these young girls remain in the sites where these sexual violences occurred, the survivors bodies and remaining physical trauma. Through their testimonies they are made visible.

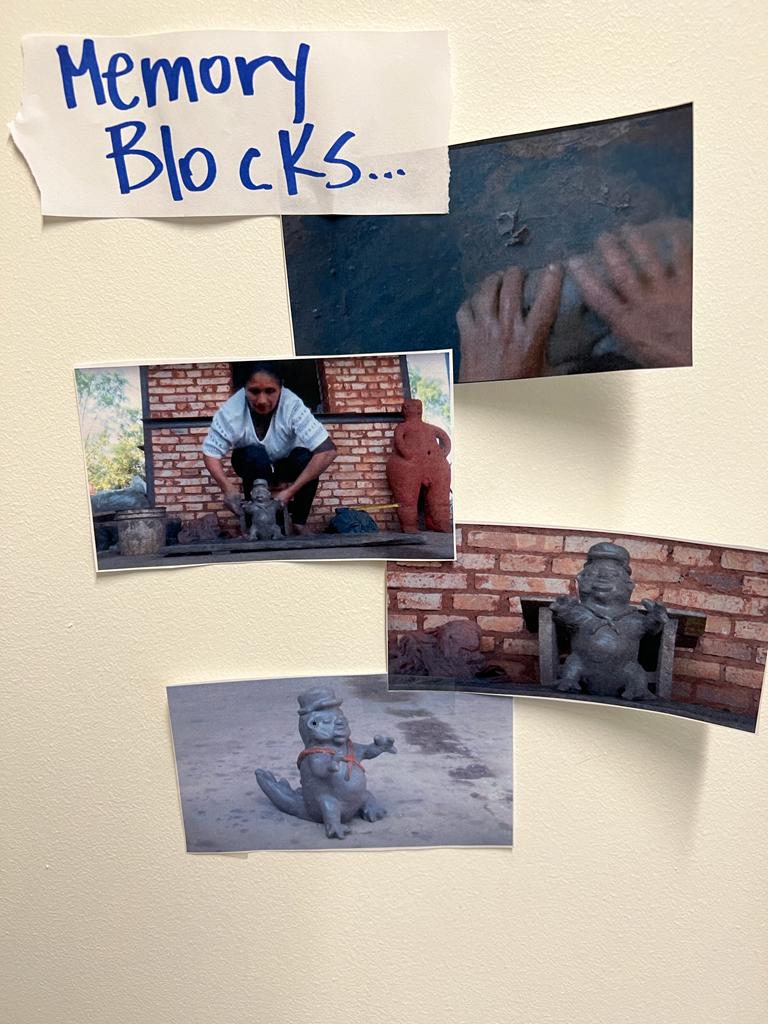

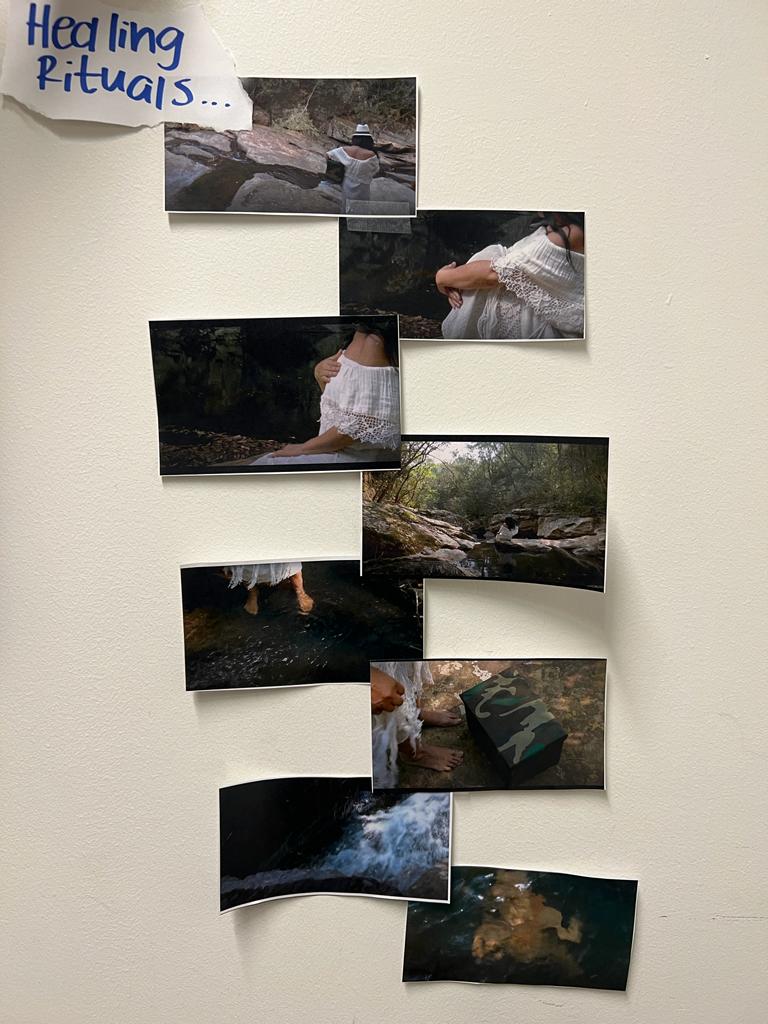

Through the stills pulled from the documentary I will showcase how the artwork created in the film could serve as a healing tactic for the viewer and victims. In addition, the testimonies as a healing modality. There are two timelines operating in Calle de silencio (2017) that illustrate the healing that is available through the production of this film and the victims testimonies. One thread throughout the film is the ceramic making scenes which are overlaid with the testimony and stories being told in the background. The opening scene is a woman who is making a piece of art with clay (Figure 6). Which is also a traditional art making practice in Paraguay. I never really learn who she is. At the end of the credits she is identified as a mujer artesana (artisan woman).

Figure 6. Delicia Alarcón’s intervention.

The performance of the ceramic piece is a thread throughout the film that showcases her making a lizard like creature which I think represents the military subjects who were the aggressors against these young girls. She wraps a red scarf on the lizard to showcase the political affiliation of the regime: los colorados. Then the woman dressed in white takes this lizard into the forest and has a ritualistic experience by the water all alone (figure 7).

This character is possibly taking this lizard as an offering. However, towards the end of the film we see this woman drown the frog (figure 8). This act of drowning an inanimate object performs and signifies the regime and military personnel. In this moment the ritualistic choice to drown the lizard indicates a certain mode of agency. This individual has taken something rather painful and decided to get reparations by their own accord.

As the woman’s storyline happens, a victim of the sexual violence narrates her experiences. I see her silhouette however I never actually see her face. This anonymity shows me that the fear of showing her face is still present even though this woman has grown up, survived, and built a family of her own. She specifically names Colonel Leopoldo Perrier alias Popol as one of the main aggressors in her lived experiences.

Figure 7. Delicia Alarcón’s second intervention.

Figure 7. Delicia Alarcón’s second intervention.

Towards the end of the film she states,

“Me hace bien contarte” (It helps me tell you)

“Que no se te borra” (for it to not be erased)

“Una sombra eterna es” (it’s an eternal shadow)

“Recordar de nuevo duele” (to remember again; hurts)

“Hay que seguir adelante” (we must keep going forward)

Her account of telling her story expands the notion of storytelling as healing. Even though she chose to remain anonymous with her face not fully present her body is present and her voice speaks her truth. She returned to tell her story and chose to actively tell what happened to her however she can only appear as a shadow even though she is not a disappeared child anymore. She can only introduce herself as a shadow. As a result, I wonder where is the shadow from? who is the shadow of? Is it the state, the military regime? the victims? or the survivors?

Delicia Alarcón

To watch the whole documentary follow this link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=te0K-UfphEg&t=562s

Political prisoner and systematically disappeared – the case of Agustín Goíburu (Asunción, Paraguay 1977)

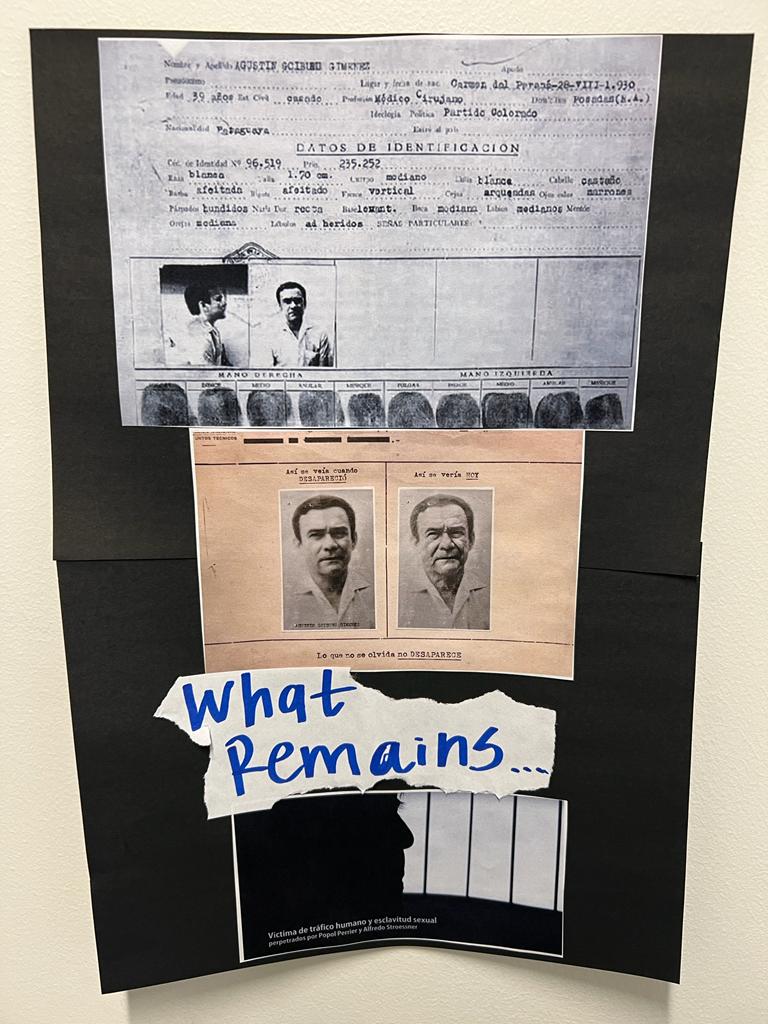

Lo que no se olvida, No desaparece (What is not forgotten, doesn’t disappear) is written in a The theme of political imprisonment is explored with the police record of Agustín Goíburu. He was a doctor and political leader of the “Movimiento Popular Colorado (Mopoco)”fierce opposition to the Alfredo Stroessner regime in Asuncion, Paraguay (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Delicia Alarcón’s third intervention.

Figure 8. Delicia Alarcón’s third intervention.

Consequently, his police document from the Archivo de Terror (Archive of Terror) in Asunción indicates that even though he was captured and violently disappeared by the military regime, he was a renowned doctor and political activist in his community (Figure 10). In November 1969 he was first kidnapped in río Paraná, Argentina while fishing with his 11 year old son, Rogelio Goiburú. He was taken to Asunción and disappeared for several months until he was able to escape with the other political prisoners and live in exile in Chile. In 1970 he was able to return to Argentina. On February 9, 1977 he was kidnapped again in broad daylight in the city of Paraná, in the Province of Entre Ríos by the Argentinian repressive forces that worked closely with the Paraguayan armed forces. He was forced into a vehicle and taken to the detention torture centers. In a clandestine way he was moved to the Department of Investigations in Asuncion where he systematically disappeared by the military personnel. He was last seen during holy week in 1977. Figure 11 showcases the last family photo where Agustín Goiburú was present in 1976. Today, there are mass exhumations happening in efforts to locate his physical body, bones, and any remnants of his existence. His son Rogelio Goiburú is the current director of Memoria Histórica del Ministerio de Justicia (Historical Memory Ministry of Justice) who is leading the charge of mass exhumations in efforts to locate disappeared bodies. In addition, there is a committee of truth and justice that are working to locate his physical remains and other disappeared bodies that still exist in mass graves somewhere in Paraguay. Until Agustín Goiburú’s body is found and his bones and identity verified he is still “disappeared”. However, as we have stated what remains of his existence are in the family images, his children, and his legacy as a political prisoner in the official state Archivo del Terror (Archive of Terror).

Delicia Alarcón

https://plancondor.org/node/1307

Works Cited

Aguilar Gil, Yásnaya E. “Nosotros sin México: naciones indígenas y autonomía.” Nexos, May 18, 2018. https://cultura.nexos.com.mx/nosotros-sin-mexico-naciones-indigenas-y-autonomia/.

Bandelier, Adolph A. F., and Fanny R. Bandelier. Historical documents relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and approaches thereto, to 1773; Spanish texts and English translations. Washington: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1926.

Caruth, Cathy. “Preface.” Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Castañeda, Michelle. Disappearing Rooms: The Hidden Theaters of Immigration Law. Durham: Duke University Press, 2023.

Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular / Programa por la Paz (CINEP/PPP). Colombia: Deuda con la Humanidad 2: 23 años de Falsos Positivos. Bogotá: Editorial Códice Ltda, 2011.

Cnmh. “«Mujeres con las botas bien puestas»: las madres de Soacha quieren contarle al mundo su lucha contra la impunidad.” Centro Nacional De Memoria Histórica, May 24, 2023. https://centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/mujeres-con-las-botas-bien-puestas-las-madres-de-soacha-quieren-contarle-al-mundo-su-lucha-contra-la-impunidad/.

Cnmh. “29 años desaparecidos – Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica.” Centro Nacional De Memoria Histórica, March 16, 2020. https://centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/29-anos-desaparecidos/.

Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. “Buscador de Jurisprudencia,” n.d. https://www.corteidh.or.cr/cf/Jurisprudencia2/ficha_tecnica.cfm?lang=es&nId_Ficha=46.

El Espectador. “Palacio de Justicia: ‘El Día Que El Fútbol Ocultó El Holocausto’| El Espectador,” November 6, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xH8Udg581AI.

Freud, Sigmund. “Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through.” In Further Recommendations in the Technique of Psychoanalysis: Recollection, Repetition, and Working Through. 147-155. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1924.

Giraut, Frederic. “Naming the Conquered Territories: Colonies and Empires – Beneath and Beyond the Exonym/Endonym Opposition”. In The Politics of Place Naming : Naming the World. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2022.

Gobierno de Sonora. “Boletín oficial: Tomo CCXXII, número 27, sección I.” Hermosillo, Órgano de Difusión del Gobierno del Estado de Sonora, October 2, 2023. https://boletinoficial.sonora.gob.mx/images/boletines/2023/10/2023CCXII27I.pdf.

Gómez Retana, Denisse. “El carácter político de nombrar para la Nación N’dee/N’nee/Ndé.” La Verdad, September 14, 2023. https://laverdadjuarez.com/2023/09/14/el-caracter-politico-de-nombrar-para-la-nacion-ndee-nnee-nde/.

Herman, Judith Lewis. Truth and Repair: How Trauma Survivors Envision Justice. New York, NY: Basic Books, Hachette Book Group, 2023.

Idrobo, María Camila. “Palacio de Justicia: 36 años sin encontrar a los desaparecidos,” n.d. https://www.radionacional.co/actualidad/palacio-de-justicia-36-anos-sin-encontrar-a-los-desaparecidos.

Izagirre, Ander. “Así se fabrican guerrilleros muertos.” El País, March 26, 2014. https://elpais.com/elpais/2014/03/06/planeta_futuro/1394130939_118854.html.

Longoria Granados, Juan L. “¿Cuántas tribus N´dee/N´nee/Ndé hay? Sobre las 9 parcialidades apaches mencionadas en documentos del siglo XIX.” In Vol. 4, Memorias del IV Coloquio Internacional de las Culturas del Desierto. Ciudad Juárez: Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología. 2020: 17-32.

Merton, Jack. Acculturation: Psychology, Processes and Global Perspectives. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers, 2014.

Revista Semana. “Los casos olvidados de los falsos positivos.” Semana, September 2, 2020. https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/los-casos-olvidados-falsos-positivos/119416-3/.

Rae, Real Academia Española -. “falso positivo.” Diccionario Panhispánico Del Español Jurídico – Real Academia Española, n.d. https://dpej.rae.es/lema/falso-positivo.

Singh, Julietta. Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017.

Smith Castro, Vanessa. Acculturation and Psychological Adaptation. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2003.

Taylor, Diana. Disappearing Acts. Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

Taylor, Diana. “Tortuous Routes: Four Walks through Villa Grimaldi” ¡Presente!: The Poetics of Presence. 175-202. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

Terrazas Sánchez, Filiberto. La guerra apache en México. Ciudad Juarez: Universidad Autonoma de ciudad Juarez, 2010.

Tribunal Superior del Distrito Judicial de Bogotá. “Sentencia condenatoria del General Jesús Arias Cabrales en el caso de la toma del Palacio de Justicia,” October 23, 2013. https://www.derechos.org/nizkor/colombia/doc/palacio30.html#l18.

Van der Kolk, Bessel A.. The Body Keeps the Score : Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books, 2014.

Zona Free. “Chihuahua se niega a reconocer a la nación N’dee como pueblo originario.” August 4, 2023. https://zonafree.mx/2023/08/04/chihuahua-se-niega-a-reconocer-a-la-nacion-ndee-como-pueblo-originario/.

Zona Free. “Coahuila y Sonora reconocen los derechos de la Nación N’dee. Chihuahua se los niega.” Zona Free, October 20, 2023. https://zonafree.mx/2023/10/20/coahuila-y-sonora-reconocen-los-derechos-de-la-nacion-ndee-chihuahua-se-los-niega/?fbclid=IwAR1a3-i5CnFS4qflm_9HWtQxuKRwFM_xnckgYDz77yiooprXEq2QYQHcHt8.