Traumatic Dis-appearances: That Which Refuses to Disappear

Group Members:

Delicia Alarcon, Juan Arias, Grecia Márquez García

Our work and creative project will center around systemic dis-appearances of marginalized communities. For the conquerors as much as for the Spanish “explorers,” controlling the Indigenous populations was necessary to integrate them into colonial life and to get them to work for them (whether in conditions of supposed “freedom” or as slaves). Pacification and reduction were two practices through which they exercised this control. Both are euphemisms, the first referring to the process of assimilation into Christian life through evangelization and acculturation and the second to the persecution, massacres, and forced displacement of communities and individuals in resistance. Thus, identities were lost, and nations were dismembered.

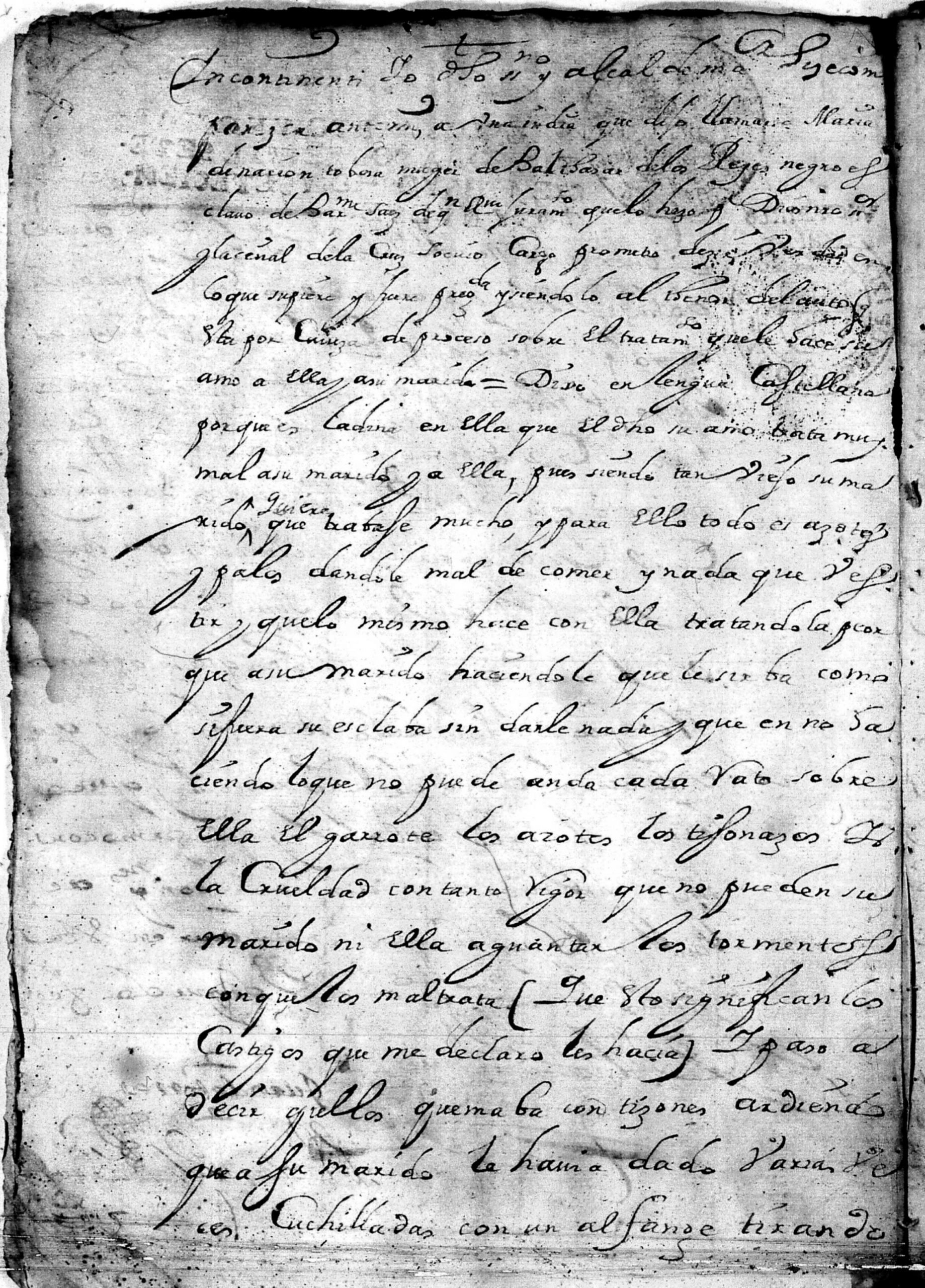

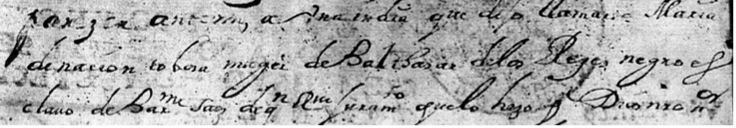

Throughout our research and conversations around “disappeared” communities, our colleague Grecia Márquez shared the story of Maria. In 1712, a woman named Maria appeared in front of the Royal Court in New Mexico seeking to resolve a case of torture by her partner’s master. In the documents, we learned that she was a free woman, her spouse a slave, and in her declaration, she presented herself as a member of the Toboso Nation (see Figure 1 & 2). This statement is significant because, according to various records in the colonial archives as well as contemporary historians and anthropologists, this nation was already considered virtually extinct at the beginning of the 18th century. In the mid-19th century, there are still records of Toboso people in the region that later became Chihuahua, Mexico. However, the records began to diminish, and eventually, the baptismal certificates stopped registering people from Indigenous nations, replacing their native names with the category of “Indian.”

The current official report of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) can be consulted, where ethnicities with “greater roots” in Mexico are registered, and the Toboso category does not appear. Likewise, the 2020 report is more detailed than the last one presented in 2022, in which many nations are no longer mentioned. In contrast, in the instructions for filling out census surveys of the same institute in 2015 on their online page, they register the Toboso language as an option. We ask ourselves about the origins of this official position that, at the same time, recognizes and denies existence. In conversation with the Ndé (nation known as Apache) historian Juan Luis Longoria Granados about the project of the community to which he belongs to identify other Ndé people, he shared with Grecia that in 2019 three families of Toboso people were identified in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. This makes us think about what it has meant for this community and nation to have been cataloged as virtually extinct by the viceregal government and by the republic, as well as by contemporary historians and anthropologists.

Beyond an accurate description of how these two disciplines use the term (virtually extinct nation), we wonder about the ideologically charged implications, the tangible effects on institutional recognition, and other terrible social violence inflicted on these peoples. On the other hand, we question, “How it is possible to go through all these epistemic and concrete violences and still be able to recognize oneself as that which is supposedly extinct?”, “How does memory work against official records?” and “How is it embodied and performed in order to survive?”. This is one concrete case and example of what we would like to address in this project. Although the other cases will differ in time and space from this one, our project will be driven by these questions. Some questions we will continue to process throughout this project: “What does it mean to disappear individuals and communities?” “Is it even possible to make someone disappear without leaving any traces behind?”

The Toboso case allows us to understand the processes of systemic disappearances. As a group we face a paradox: Is it possible to completely disappear someone or a community? The texts on trauma that we have been reviewing in class also help us expand this question. If, according to Freud, what is repressed, although forgotten by memory, remains in the body, we can also suppose that what is “reduced,” what is attempted to disappear, also leaves traces or reminiscences in other bodies in other communities and in the earth. In that sense, systematic disappearance is nothing but another fiction whose purpose is to control populations in order to impose an identity and a history. In this case, the white Eurocentric standard of being and existing.

Ultimately, “disappearing” carries with it a political purpose. Naming something or someone as disappeared implies that those who feel identified or represented by a certain community or individual cannot, out of fear or lack of representation, contest the practices of the state. Likewise, we do not want to deny the violence behind this social practice. Disappearing, in many cases, implies killing, kidnapping, erasing and excluding from the archives, denying, denigrating, invisibilizing, that is to say, ningunear, specific peoples.

However, the void left by what “disappears” is not entirely empty. When Gloria Anzaldúa explains that the “I” is just a part of a person’s psyche, she is referring to this. Everything that happens around us leaves a trace in us, even if it is unconscious. This is why Judith Herman explains that trauma always carries a collective weight, even if it is sometimes experienced individually. Trauma remains not only in the victims and the victims’ relatives but also in the individual and collective bodies that are inscribed within this systematic violence.

Grecia learned of the violence to the Toboso nation because her father told her that a great-grandmother of hers was from that supposedly disappeared community. With Grecia, we ask: “How much of the trauma of this nation remains in her and her father’s body?” “How does the Toboso community linger in her even though she consciously does not know that culture?” To unpack Connerton: “what is ” incorporated” in the body of Grecia that sustains the attempt to “reduce,” to “disappear,” the Toboso nation?” “How does the trauma of Racism manifest itself in people who self-identify as mestizo?”

Drawing from these questions, our project not only wants to review processes of systematic disappearance in Latin America but also to trace what disappearances leave behind. We are not only thinking about contemporary Latin America but also colonial Latin America. Relying on the concepts of trauma, memory, and performance of Freud, Caruth, Herman, Van der Kolk, Hirsch, Anzaldúa, and others, we want to disrupt, problematize, and disturb the idea of disappearances in two ways. On the one hand, we want to emphasize that disappearance implies a much broader process than killing people. It is always part of a political, economic, and social project. On the other hand, disappearance is never absolute– that which is attempted to disappear always leaves a trace. Nothing disappears completely.

As an entry point to this work, we will use the case Grecia found in the Archivo de Hidalgo del Parral from the University of Arizona about the Toboso nation as a primary example. We will divide the group work into investigative writing and research which will inform our creative product. We will all participate in the general process of information gathering and production of the cultural artifact we plan to create after our collective research. Each of us will look for specific cases of disappearances in their country of interest– Grecia in México, Delicia in Paraguay, and Juan in Colombia. We will use these findings as a foundation for our research and creative elements of the project. Since Grecia has the initial contact with the Toboso information, she will be in charge of the research to get more information about this community and what it looks like in the present day. She will try to contact some of the Toboso-identified people from 2019 to support and inform our project. Delicia will be in charge of translations from Spanish to English, and the editing process to ensure our process, research, and creative elements align with course materials. Juan will be in charge of developing the creative component and expanding on our initial ideas proposed as a group. In the meantime, we have a first image: silhouettes of bodies traced with objects that can contain memory, such as ashes, flowers, candles, clothing, soil, and other trinkets. Likewise, we would like to use the case Grecia found about Maria in the archive (Archivo de Hidalgo del Parral from the University of Arizona).

Figure 1

Figure 2

[hize com]parezer ante mi a Una india que dijo llamarse María/ [I made] appear before me an Indian who said her name was Maria

de nación tobosa muger de Balthasar de los Reyes negro es/ of Toboso nation woman of Balthasar de los Reyes black

clavo de Bartolome Saez de quien hise Juramento que lo hizo por Dios nuestro señor/ slave of Bartolome Saez who swore in the name of God to tell the truth

Series of Depositions Concerning Bartolome Saez’ Mistreatment of His Slaves, Servants

AZU Film 0318 rl. 1712, fr. 0486

References:

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Light in the Dark/Luz En Lo Oscuro. Duke University Press EBooks, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822375036.

Connerton, Paul. How Societies Remember, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 1989.

Freud, Sigmund. “Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through.” Standard Edition 12 (1950): 145-157.

Herman, Judith L. Truth and Repair. How Trauma Survivors Envision Justice. New York, Basic Books: 2023.