Delicia Alarcon

Weekly Response

11/06/2023

dda8357@nyu.edu

Legacies of Political Disappearances as political terror

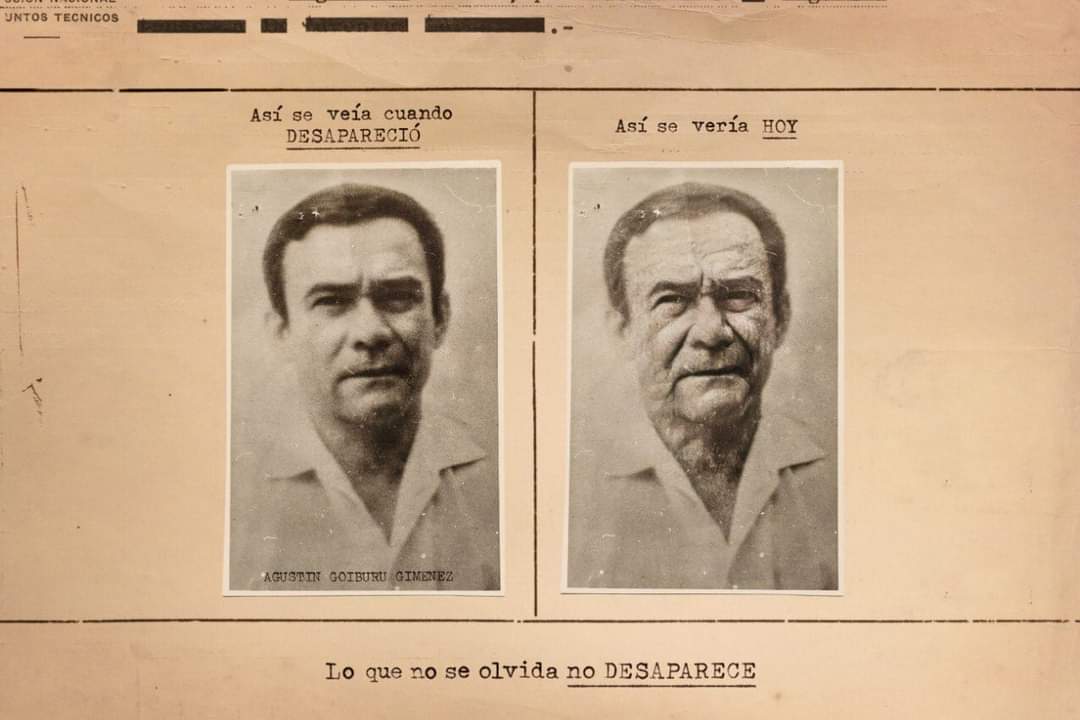

The two readings for this week were situated in two different countries – Argentina and Chile. The reading on H.I.J.O.S discussed the physical body as an archive and the use of photography as proof using the example of Las Abuelas y Madres de Plaza de Mayo. The reading on Villa Grimaldi situates memory and trauma in a physical space. Not only the ritualistic movements of the abuelas with the images of their children but also the physical spaces of torture that are now sites of memory. While reading “You are Here” H.I.J.O.S and the DNA of performance I kept thinking about protests and las abuelas movements as ritualistic. Their repeated motions set the tone for their activism. Diana Taylor in her work The Archive and the Repertoire states, “ritualistically, they walked around this square in the heart of Argentina’s political and financial center. Turning their bodies into billboards, they used them as conduits of memory. They literally wore the photo IDs that had been erased from official archives” (170). The Abuelas used their physical bodies and the photo IDs as proof that the children had disappeared. They demanded the children to return home alive.“The children represent themselves as the conduit of memory” (185). Similarly, in Asuncion, Paraguay during the Stroessner Regime there were many desaparecidos. One notable case is Agustín Goiburú who was a doctor and also part of the protest movement MOPOCO was disappeared and is still disappeared. His son Rogelio Goiburú who is the director of Reparación y Memoria del Ministerio de Justicia is on a quest to find the physical bodies in the fosas comunes. In the archive in Paraguay his police documents says on the bottom “Lo que no se olvida no desaparece” (what is not forgotten doesn’t disappear).

Therefore, the pictures, bones and sites of torture remain as living memory and become archives in their spaces. In the Villa Grimaldi reading I loved the question posed: “How, and for whom, does a memorial site bring the past into presence?” (175). Just as “The Madres turned their bodies into archives, preserving and displaying the images that had been targeted for erasure” (Archive & the Repertoire, 178). Villa Grimaldi and Diana Taylor’s visceral experiences reminded me of my own experiences in the Museo de Memorias in Asuncion, Paraguay this past August. The site of memory that used to be a police station used for torture during the regime has become a museum and site of memory. People come and do a tour of the different sections of the police station. There was a moment the guide wanted me to enter the jail cells to see where people had been tortured. I could not physically move into that space since my own grandfather experienced this type of torture at the hands of the regime. My body in that physical space had become a conduit of memory. My DNA in a way was activated in that space and as Diana Taylor states, “Trauma lives in the body, not in the archive” (201). I would expand this statement because I believe that Trauma does exist in the archive and the archive has the DNA of performance with the photographs of the police cards or “fichas policiales”. Seeing these images in the archive reactivate memory and thus reactives trauma. Yes trauma lives in the body and like both mine and Taylor’s experiences in these sites of memory trauma can be transmuted and activated. Much like a space of memory activates a physical body the images in the archive can also activate trauma and memory. Our bodies thus become conduits of memory and transmission of that memory.